Ghostwriter

It was a few days after Christmas in 2015 when I snapped on the light – a no-nonsense naked bulb screwed into a ceramic wall socket at the base of the stairs – and started down to the basement of my childhood home, intending the impossible.

A Basket of War Letters

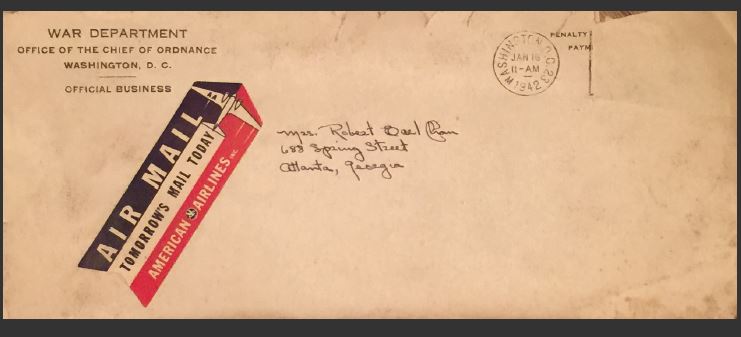

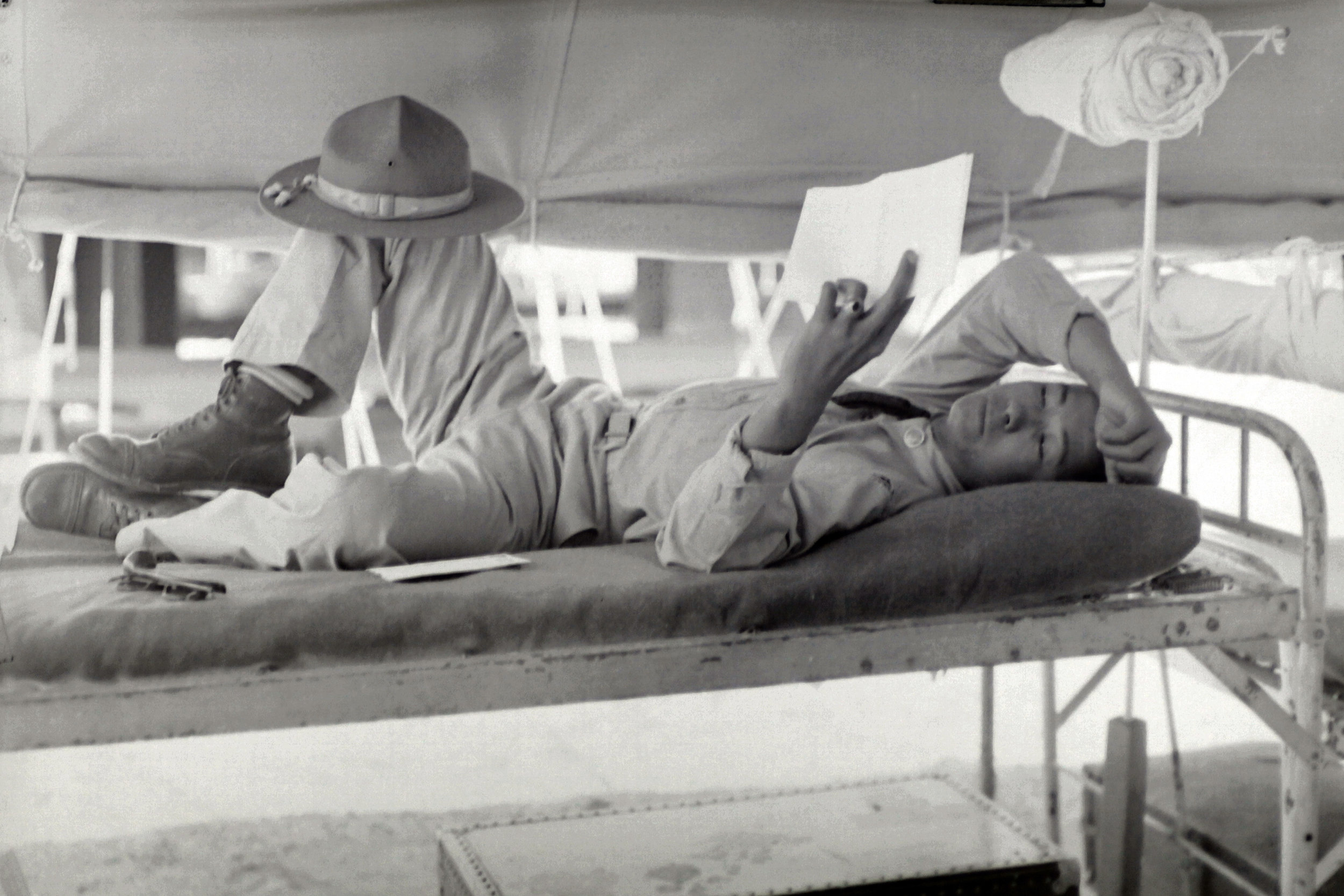

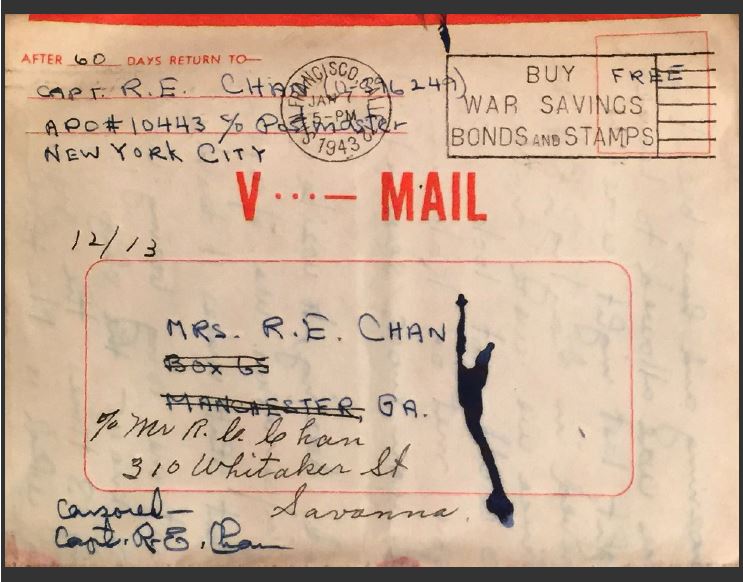

I wanted to find a letter I had last seen some 30 years before that Dad had written to his first wife, Gretchen, from the Indian or Burmese jungle in World War II. He had signed it, “Earl and Gus” and next to Gus’ name was a tiny, perfectly human-looking hand print. It belonged to a small monkey – perhaps a young macaque separated from his mother – that had accompanied Dad in his tent and around camp in the China-Burma-India Theatre for a few months and liked to eat bits of banana from Dad’s hand and to ride on his shoulder. I remembered the letter came from a basket full of other letters – on thin crinkly paper, yellow and brittle, often water-stained, and many still in envelopes with red stripes on the edge. At ten, when I had found the basket, I was only mildly interested in these other letters. I noted them but wanted principally to find out more about who this “Gus” character was. Now, at 42, I was descending into the gloom to find the Gus letter to share with Dad … but by God, I knew enough of what lay ahead that I needed to find those other letters now, too. For me.

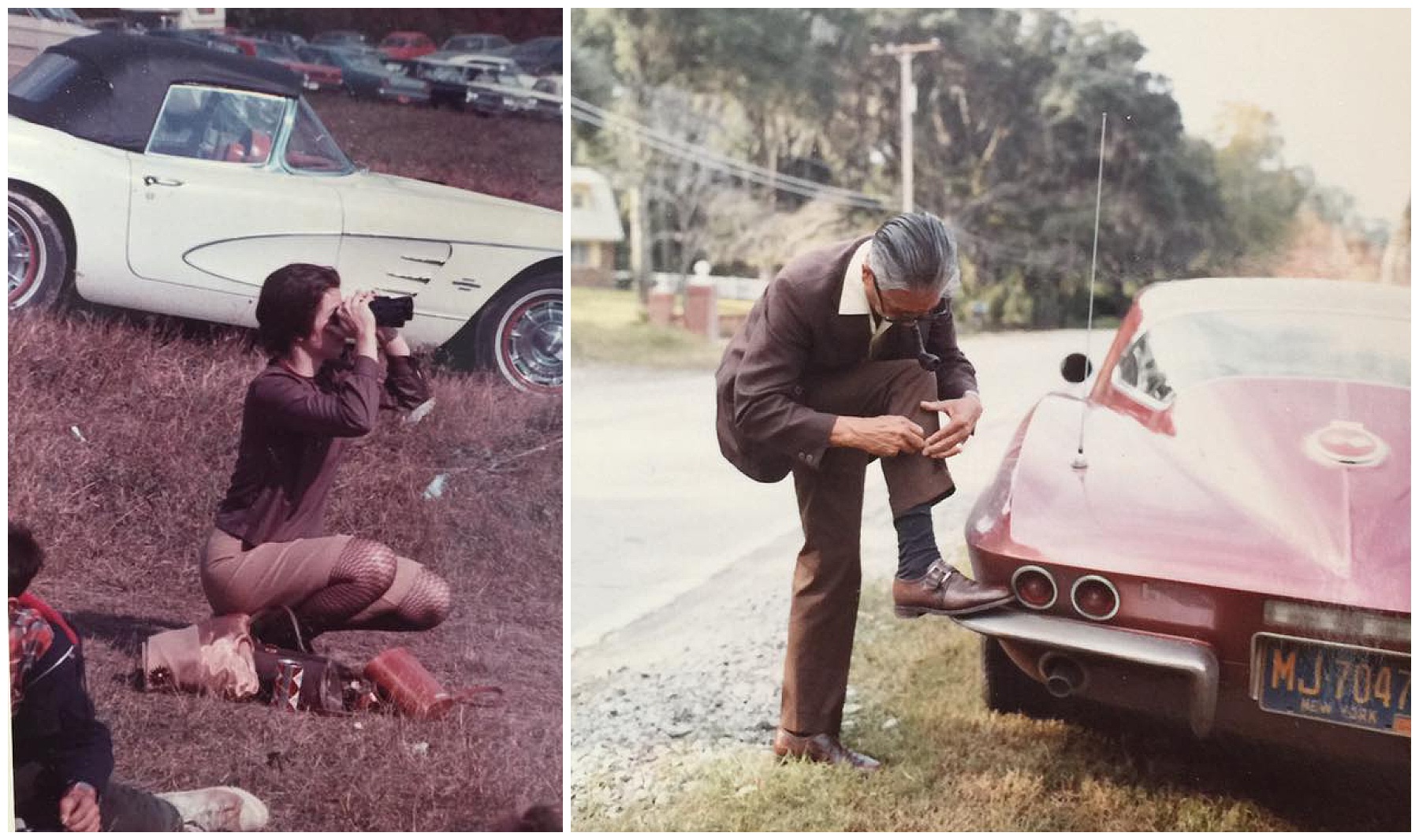

Now, in the 1970s, my parents were stylish and social. Turtlenecks and blazers for him, gold velvet dresses, silken jumpsuits and strappy sandals for her. They both drove corvettes - his red and hers white. They were on the local bowling team and were serious enough to have their own balls, taking care in polishing and maintaining them, and keeping them stored in striped and pungent vinyl cases that opened from the top like old doctors' bags. His ball sparkled in mesmerizing, riotous swirls of deep burgundy red, while hers was a cool blue. There is no mistaking the personalities behind these color choices.

My parents were not each other’s first loves, but were certainly each other’s last and deepest ones. Together they read Edgar Cayce and threw meditation parties. They made Swedish meatballs and threw bridge parties. They frequently had Christmas parties and sometimes they threw just-because parties. It was as though they were just so darned happy to have found each other and gotten another chance that it all spilled out over everything. Fondue and dancing could frequently be had in the basement of our mid-century modern, split-level ranch house. They held each other close and danced cheek to cheek.

That was in the 1970s. Here in 2015, though, Mom was gone, Dad was going on 102 and confined mostly to his overstuffed lift-chair up in the living room, and the basement was a dark and musty catch-all for 50 years of junk. I found myself stepping gingerly on piles of scrap wood from forgotten projects; and around toppled piles of books and magazines. Dad had the complete set of some 50 years of Playboys he thought might be worth something someday, and Mom had the same for National Geographic. Bolts of silk from Mom’s silk painting business, Chance Designs (emphasis added), spilled dustily from plastic shelving erected helter-skelter – the ruins of several failed attempts to stem the rising tide of mayhem. Meanwhile her sewing station was barely visible – just open space enough for a chair and a machine, if you could get in there - in the eye of a hurricane of paisley, calico and checks dating to the last time she had actually used it.

Next to this, were Dad’s old hip-waders and fishing baskets draped on a jury-rigged coat rack of sorts, leaning precariously to one side. I had discovered his tackle box, which was impressive, when I was about 8. I was most taken with the artificial lures - gummy worms that stuck moistly to my fingers, and the colorful and iridescent crank- and spinnerbaits made to look like minnows. They looked like toys and smelled wonderfully industrial.

I did not recognize the real treasure inside, however, which was Dad's beautiful and delicate handiwork in fly-tying. He tied fur, feathers, threads and other materials to hooks to mimic the look of natural prey - which could be anything from insects to crustaceans, worms, minnows, even amphibians or vegetation. Because each fly was tied for a specific target species, this activity required that he know a fair bit about his quarry - its behaviors and quirks, and how it went about being in the world. It required imagination and being able to get inside the head of an elusive creature. There was strategy and creative problem-solving involved. In short, fly fishing was made for Dad. And although the War turned him off of guns and hunting forever, he never lost his taste for standing in a cold stream and casting a line out into the current.

“When I go fishing the fish just crawl up on the bank and open their gill for my string. They know it’s no use to resist.”

A random collection of the most popular home exercise equipment also hearkened back to more optimistic days. There was an old rowing machine under a good 2 millimeters of dust; a Nordic ski-track, with lines hanging slack, the skis askew; a five-spring chest expander that as far as I knew, no one in the family could expand; and although I couldn’t see it at the moment, I knew that somewhere around here, there was a Thigh-Master too.

This was not the first time I had tried to find the letter from Gus. Over the years, I had searched for the basket a number of times, but to no avail. I never saw it again and Dad seemed to neither know nor care much where it could be. Until the very end, when his early memories were his most vivid, he was never one to dwell in the past and had a most infuriating and unromantic way, I thought, of always looking and moving forward. Which is why my current intention to go and find these letters seemed doomed from the start. I cannot explain it, though. I simply knew that for the first time in 15 years, I was going to go look for Gus again and I just had a hunch that I was going to find him.

As it turned out, Gus is the only thing I didn’t find. What was waiting for me in the fondue-palace-turned-domestic-landfill, was the basket of letters – exactly as I remembered them, and inexplicably, indeed unbelievably, sitting right out in the open, on the edge of a waggle-legged side-table that should have been thrown out in 1979. The lights were blown in the back party room and my flashlight fell on the basket like a spotlight. I was immediately struck with the amusing image of the singing frog from Loony Tunes, tap dancing and kicking his way across the stage, shouting out “Hello my darling, hello my baby, hello my Ragtime GAAAaaal” and then falling abruptly back down into a mute lump as soon as anyone looked at him. The basket was like that - mum, but heavy with song. An invitation. A prince in frog's clothing.

I did not find the Gus letter, which had been separated from the basket (by 10-year-old me?), until over a year later. It was not as magically wonderful as I remembered it to be, to be honest.

As with the tackle box, the real treasure was elsewhere: almost 300 letters, opening on November 25, 1941, with a young man bursting at the seams trying to plan a legal marriage to his first wife (and my brother’s mother), Gretchen, who was white. The couple would have to marry in D.C., because their home state of Georgia was one of many that still had strong anti-miscegenation laws. The letters proceed to the bombing of Pearl Harbor two weeks before the wedding, his call into active duty, throwing everything into question and chaos, and then follow his entire career in the China-Burma-India Theatre, tracking his rise from "2nd Louie," as he called it, to Colonel in the U.S. Army. At each advancement, he promoted Gretchen to the rank above himself, in hilarious and tender fashion. The letters end with his final discharge in January 1945.

A Box of Negatives

The letters were the icing on a cake that had actually been baking for almost a year because several months earlier, my husband Brent had gone into the basement following a whimsy of his own and come back up with a box of many hundreds of large-format 4 x 5” negatives. No one knew what they could be – not even Dad, who, predictably, didn’t figure they were anything much. He didn’t remember a box of negatives. He had been an amateur photographer all his life and dabbled in professional work, doing some weddings and family portraits here and there as well as commercial food photography.

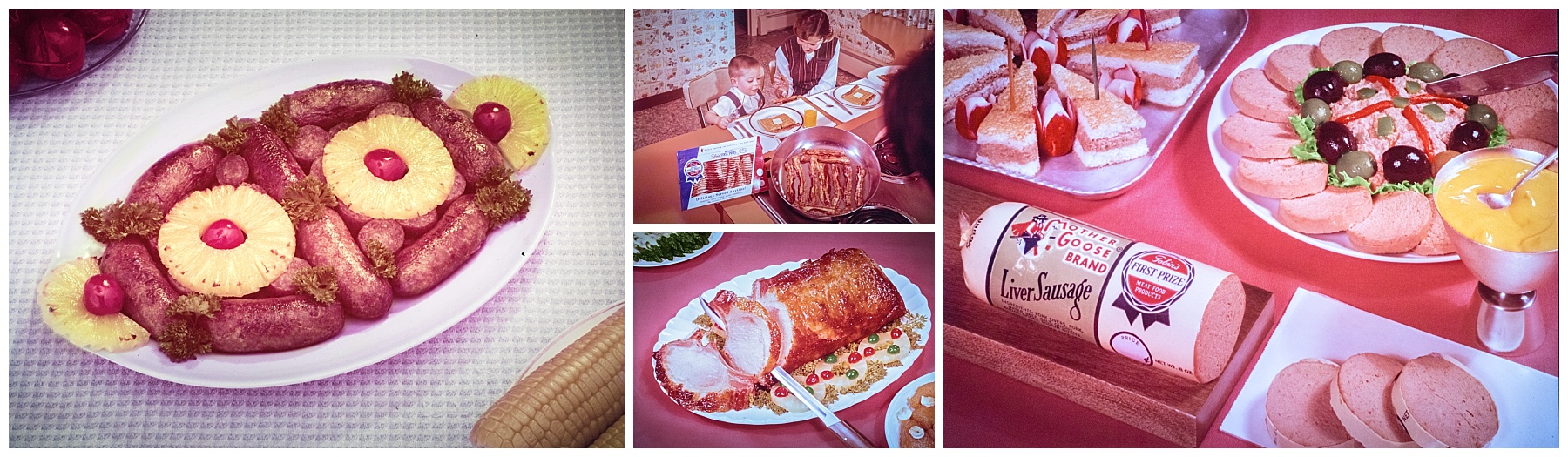

I had seen the large 8 x 10” color negatives of Shelly Brand sausage and smoked meats and Mother Goose’s first prize “meat food products." They surfed the wave of America’s post-War love affair with processed foods. There were candied-looking bone-in pork chops decorated with maraschino cherries and cored apple slices; liverwurst finger sandwiches, with olives and grim looking parsley sprigs; bologna slices, deviled eggs and cut radishes stacked in strange tiers and towers; sausages, carrots, potatoes and peas with perfectly melting butter pats – all in garish arrangements thought to be appetizing in the day. Breakfasts were especially amusing. Hearty sausage and egg platters were pictured with canned pineapple slices and cherries, and arranged into alien faces with bug eyes that made it look like your breakfast might actually be coming to eat you.

Yes, I had seen those negatives, but they were in Kodachrome color and the size of a sheet of paper. This box contained only black and white, much smaller negatives, many curled at the edges, some stuck together, visible water and mold spots throughout. I was blind to their potential because how could anything important have escaped our family’s collective consciousness till now? How could Mom, at the very least, not have known about everything important in this house, or gone to the grave without telling me about it? So I took the box from Brent’s arms with a fair amount of equanimity. More junk to sort through.

I peered and strained at the negatives all that holiday week, holding them up to the light, but without the equipment to view and convert them properly, I couldn’t make out much. I saw figures there, and some various hints at good-natured chicanery underway - enough to pique my interest, but I still couldn’t see how they related to me.

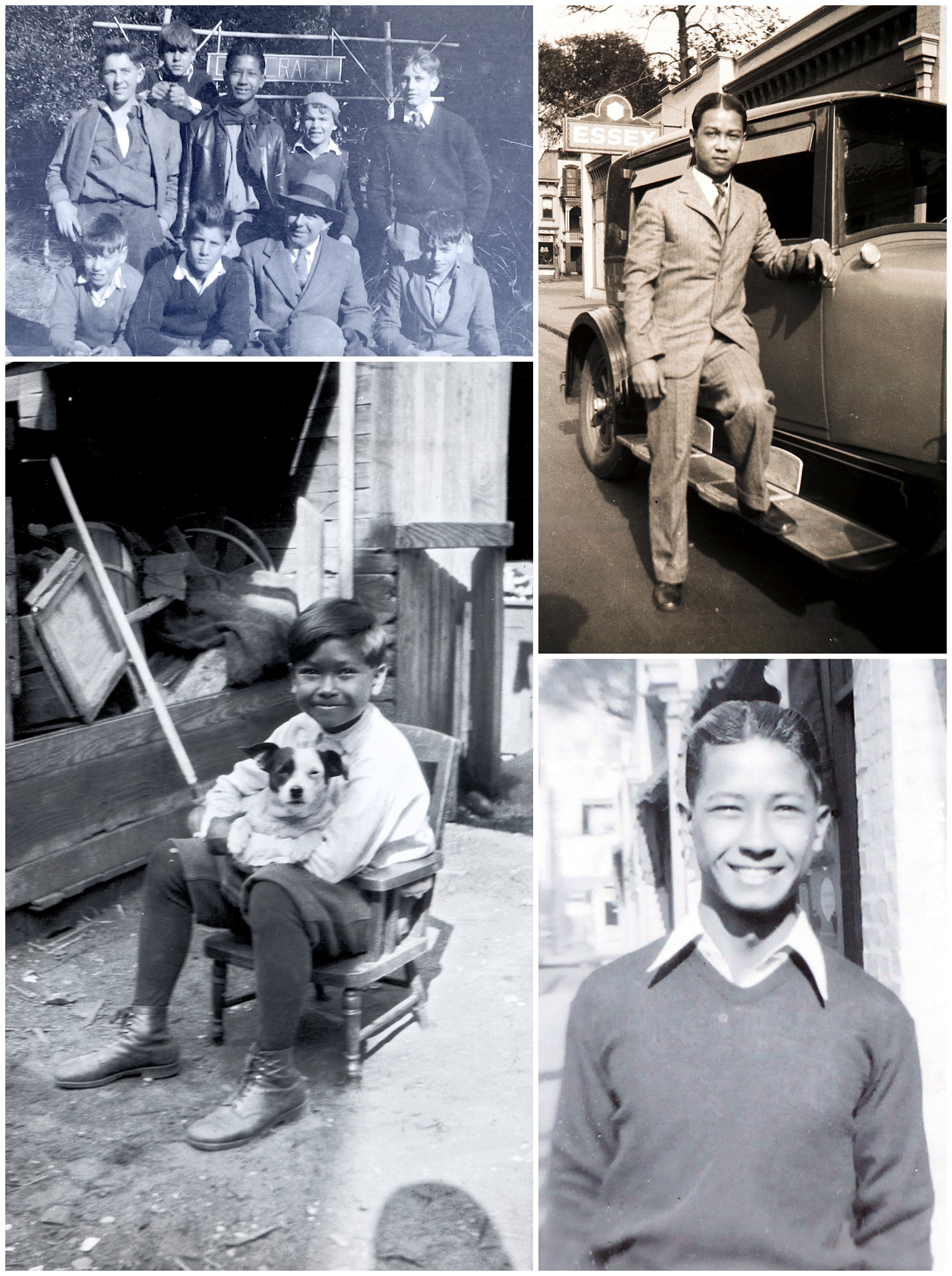

Take a moment to imagine. By the time I was in kindergarten, Dad was a senior citizen. A sharply dressed older gentleman who often looked 15-20 years younger than he was, but a senior citizen nevertheless. I had actually never seen a picture of my father as a young man, except for that 1940s army portrait, the wooden stoicism of which evoked neither an individual nor a life.

In fact, I believed that Dad had no early pictures of himself or the family. This was the Deep South at the turn of the 20th century, after all, and the family was large and fairly poor – six kids and a dozen or so employees living off the income from a Chinese laundry. And if my grandparents did take a picture here or there of the older children in Chinese robes with tassled head gear teetering, by the time the 5th or even 6th came along, who had time for costumes and keepsakes? Dad, Robert Earl Chan, fifth child, did not even get a Chinese middle name. It was like my grandparents had just thrown up their hands at that point, and still waiting on another child!

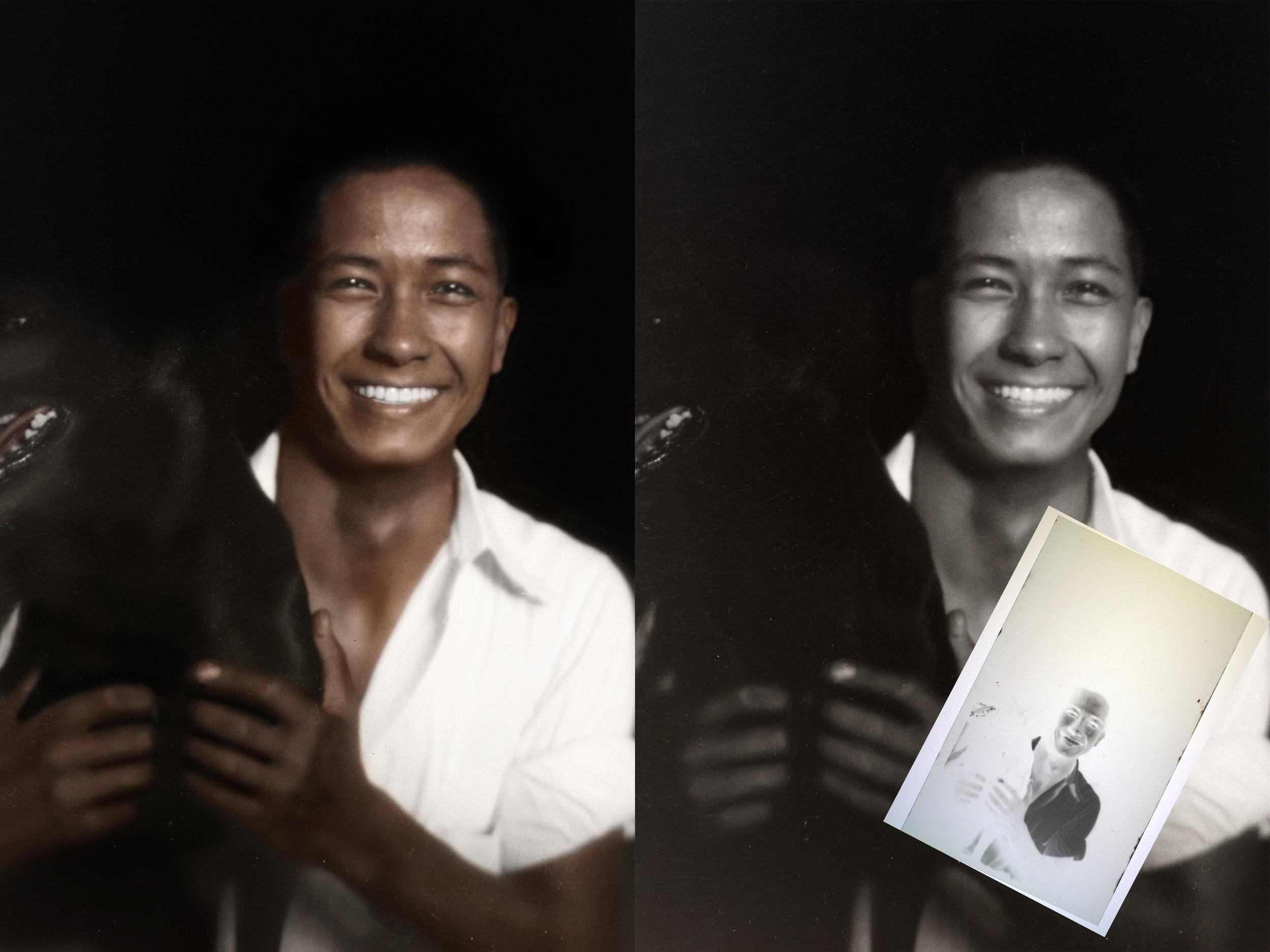

The first negative I pulled from the box was somebody smiling. But who could it be? A friend of the family? Some town person or willing photographic subject? I didn’t even have a good sense of the time period. When I got home from our Christmas/New Year’s visit, I pulled out my equipment – a macrolens, a lightbox, and Photoshop – and went to work on the smiling man first.

When I had the file in the photo viewer and hit Ctrl + I to invert the negative to a positive, the air left my lungs in a great whoosh of recognition. Champagne bubbles rose up in my chest and tickled my spine.

I would know that smile anywhere, anytime. It was the one that had beamed down on me since birth. No longer just an attractive, well-groomed older gentleman, though, this dazzling beauty, shining from his innermost recesses, and smiling at me from across the century, was Dad. It was a reassuring smile because while the man sitting upstairs was tenuously tethered to a life that was waning, this was a person fully immersed in, and saturated with, life force. This was the first negative of over 500 more still waiting in that box. Brent had found it at the peak of my dread and terror. I knew by this time, without being able to speak it loud, that we were likely entering Dad’s final year. I was only off by about eight weeks.

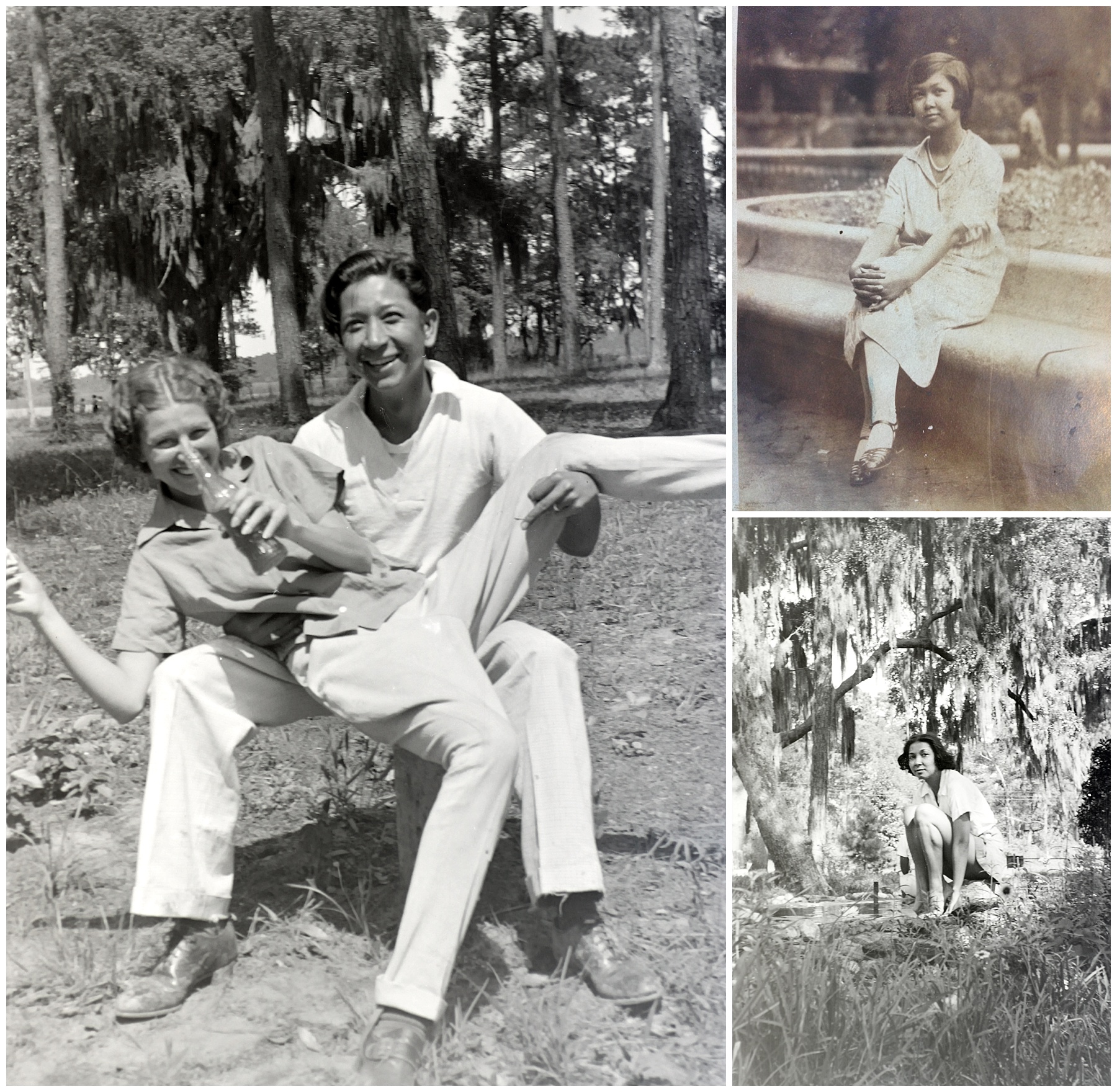

And then that box appeared, showing decades of a life lived out loud – boldly, beautifully, imaginatively and with great good humor. Pictures ranged from an early childhood in the 1910s being home-schooled in the segregated South of Savannah, Georgia; to the bombastic capers of his college years (first in the family to attend); to a young soldier in love; to the sobering and hardening effects of war; to the work of reentering civil society and the pluck and resilience needed to either pick up again on abandoned dreams, or find new ones.

“How long were you in the jungle, Dad?” I had asked one day.

“Long enough to come back a hard son of a bitch,” he had answered.

I worked feverishly, consumed for months, to digitize and convert the box of negatives. Fifty years’ worth. Looking at the pictures, as they came to life on my screen, stories I had heard over and over again began to tumble through my mind. I saw the personalities I knew so well, writ young. Uncle Sandor, the funny and gentle one, with his wife over his lap and a bottle of coke, surreptitiously flipping Dad the finger. Aunt G.G., saucy and pensive even then, I see. What lyrical language, what stories, poems and visions might have been spooling through her head, sitting right there in Forsyth Park? And this must be Sin Fah, known principally as "Sinnie." Selfish, vain, and a reported kleptomaniac in later years, relations between her and Dad, her younger brother by just over a year, were irreparably strained. I didn't expect her to be quite so lovely. Or to look so much like me.

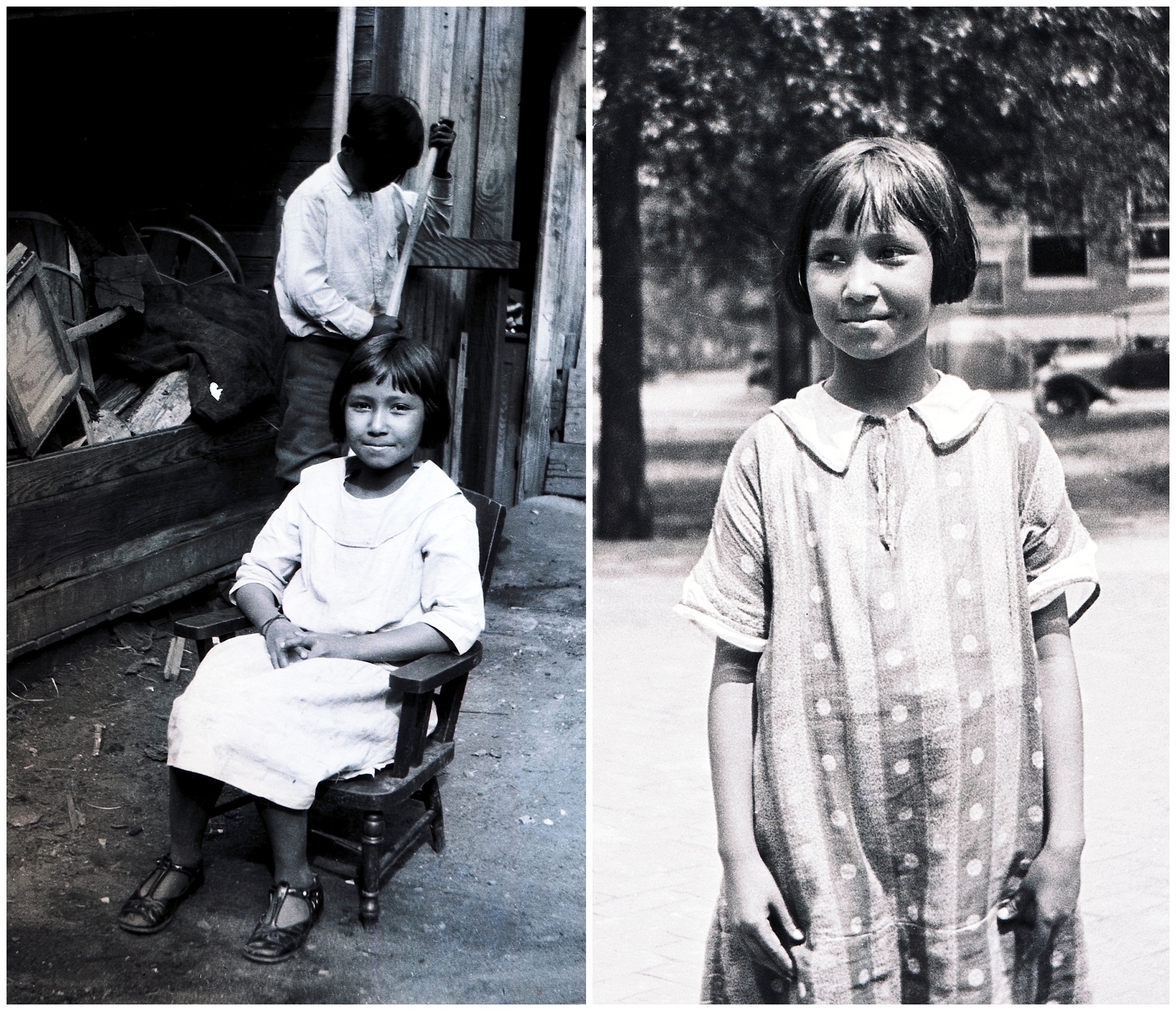

Most movingly was a little girl I couldn't place at first, always standing alone or to the side, with dimples and a close-lipped smile I could relate to immediately from my own early days as an extreme introvert. It was the smile of a girl wanting to please and to belong, but not necessarily knowing how to do it. And maybe, too, of a girl with a rich inner life barely guessed at by outsiders.

When I myself was a little girl, up to the age of 10 or 11 I would say, I felt inexplicable shame over open-mouthed smiles or laughter and went to great lengths to suppress the natural delight I found in things by making sure my teeth were covered. Why? I do not know the answer yet, but I recognized the smile in these photos as very similar to my own. I also, by a quick mental process of elimination, determined that it must have been my aunt, Bernice, the littlest of the bunch, who had died tragically as a young woman, and whose picture I had never seen.

So this was the dear little girl who had put mosquito netting over her head and walked regally into the living room one night, announcing that "A BOOOOOOtiful lady walked into the room." At this, Sandor had sarcastically remarked, "Where's the beautiful lady?" and Bernice had torn the mosquito netting from her head in a fury and stomped from the room. Dad still stewed and frowned over this moment as an old man, for he had a tender spot for children and liked to help them shine.

Sandor also liked to tease Bernice by "zapping" her food with his long musician's fingers. "ZAP!" he would cry, flicking all ten digits at her meal, which he had told her magically rendered it inedible. Grandma berated him for turning the baby off of food when so many in this world go hungry, and then turned back to the stove a moment, only for Sandor to "zap" the food again - this time silently, with exaggerated enunciation, eyes wide and brows arching to his hairline. Bernice wailed, Grandma spun around, and Sandor found out once again that the jig was up. At least until dinner. So this was Bernice. Poor sweetie. No easy thing to be the youngest of six, and shy in a family of showmen. I see you, Aunt Bernice. I know.

Dad was a rapscallion child who planted whoopie cushions and threw chairs down the back stairs and pretended to cry when he got sick of the church ladies taking up his mama’s time. Was this the chair??? And here! Uncle Archie, the steady, responsible first-born, standing proudly by the laundry’s new car. All the family dressed in their Sunday best; it was no small thing for the laundry to move from horse and cart delivery to automobile. This must have been the car Dad drove away in at the age of ten as a prank, while Archie walked up the stairs and porch, carefully smoothing his clothes, to deliver a pile of pressed shirts to a customer - wrapped in brown paper and tied neatly with string.

As Dad told it, he came around the block and saw the customer agape in the doorway, and Archie running at him from the house with raised fist, at which point he decided to just hit the gas and keep going. When he came around the block a second time, Archie had switched tactics. He stood calmly, waved, tamped his hands down in the air in a “slow down” motion, smiled even. Dad, figuring it was safe now, came to a halt and watched as his big brother strode round to the driver’s seat, opened the door to help the boy inside step down, and said “Are you okay?” Sure he was!

Dad beamed and Archie gave him two slaps, forehand and backhand, clean across the face. “WHAP! WHAP!” Dad would say, mimicking the sound, and laughing loudly at each retelling.

Another picture showed the Boy Scout with bandana tied jauntily over one shoulder. To me, he looked like a chocolate chip in a bowl of vanilla ice cream, someone you might expect in this time and place - 1920s Savannah, Georgia - to be an outsider in the group, but this was the kid who still had the charisma to get a gang of those boys together to electrify the scoutmaster’s toilet seat. He looks like a nice enough man, I thought to myself. What must he have made of little Robert Earl? And here, the mischievous teenager – look at the rakish twinkle – who flouted Miss Cubbege’s Latin homework assignment and composed a poem on the fly instead:

Darkibus nightibus,

lightibus norem;

raggibus gatepost

britchibus torem.

So damned brilliant and charming about not doing the work that all he got was a giggle, not a scolding.

The discovery of the box of negatives was the first time I understood that I had nothing to regret on Dad's behalf. People always used to drop well-meaning platitudes about his having “lived such a long wonderful life” whenever I got the courage to voice my fears that I was losing him. This bromide, while true, was not helpful and did not encourage any further sharing. Now, though, I did not just have to imagine what a long wonderful life meant; I could see it all right here before me.

Saying goodbye, I realized, is the hardest thing in the world, but I had a box of hellos here by my side to take the edge off. I received them like quenching rain.

One night in June 2017, a little over a year after my worst fear and greatest gift had come to pass, and Dad had died in my arms, I woke up at 3:00am obsessed with my burning desire to write "a book about Dad." I started scribbling madly in a notebook - aspirations, limiting beliefs, and so forth, not least of which were Dad's own words echoing back to me: "The only person going to write a book about me is ME." I had, as a result, never let myself seriously consider doing such a thing, even as I eventually grew into a scholar and an author and was given myriad opportunities to hone my craft. As an archaeologist, I wrote a book in 2007 called Slavery in the Age of Reason: Archaeology at a New England Farm (University of Tennessee Press). It was very well received, reviewed as "a beautifully written work of considerable ambition, intense curiosity and admirable inter-disciplinarity," as well as "a work of real historical significance." It is now in its third printing. I write, teach, and speak internationally, but somehow, have always felt unworthy of the task when it came to Dad or the remarkable deeds of the Chan family in America.

“One never knows, do one?”

So on this night, I got quiet and asked in my heart what he thought about me wanting to do this and waited to see what I "heard." And what I heard was this: "this is your story, Honey, and I just get to be a part of it." I was stunned. Breakthrough! It was the first time I realized that I wasn't trying to write a biography but, if anything, a memoir. Of course! How could I have missed this salient fact for so long? The seemingly insurmountable problem of how to tell another man's story was now solved, because all I really had to do was tell my own.

"You have a box of photos to see the world through my eyes," he went on, "and a box of letters to read it in my words, while you yourself are powerful and inspired. We're a great team, aren't we. Ohhhh, yeah. You know me. And you knew my heart. You knew its song and sang it back to me when I struggled to remember the words. Only fear stands in your way of so many things. I'll be right there with you every step of the way, though, if you do it. Will you do it? It ain't a bad story." And then he got sly, which was his way. "You don't really think you've been doing all this writing by yourself, do you? I'm what you might call your ... ghostwriter."

"Is that true?" I asked.

"You tell me," he said. "'One never knows, do one?'"

Like, Comment, Share!

Although the buttons below work, Squarespace is currently struggling with a bug that erases the tracking at random. Please don’t let low or no numbers shown deter you. Likes and shares still help boost my visibility, even if the numbers don’t stick around to show it. Thank you!