Mothers Don't Die

“I know I’m not the only one who thought, when you first moved here, and for years, that you didn’t have a mom. Because you only spoke about your dad,” he said.

I flinched inwardly.

The words reverberated for days. I shook them off, sometimes physically. Like a horse twitching flies away, I couldn’t bear the lightest touch. When the words came back to me, I shook my head and exhaled sharply through the nose. But flies don’t go away, they just circle and look for a better landing spot.

If you want to get rid of the flies, you’ve got to clean up the mess.

A Reckoning

“Is it true?” I asked myself. “Do I really never talk about Mom?” And then images flickered through my mind like a Rolodex, spinning faster and ever faster. Doing puzzles on my bedroom floor; riding beneath the thundering falls on the Maid of the Mist; standing on a rock overhang over the beautiful blue Danube; teaching me to knit my first baby hat; the warm softness of her hugs; the low, hesitant cadence of her voice, always searching for and finding just the right words; the chuckle that lay just beneath the surface, making her speech slightly melodic. I remembered bad stuff, too, like jerking my hand away in surly fashion, when she had laid hers on mine in comfort; the way she tried to hide the tears brought to her eyes by that bitchy move. I remembered the way she never gave full throat to her negative feelings, and would either bang out the front door “to go for a walk” or slam pots and pans in the kitchen when she was angry. And I remembered the way she never told us she was “dying,” and preferred to say cheerfully, even about terminal cancer, “This, too, shall pass.” My senses filled with all of these things, and here there are people imagining I didn’t even have a mother. “She doesn’t deserve that,” I said to myself and tried to shake myself free again.

I don’t know about you, but my emotions are housed in my body. Shame floods my chest cavity with prickling heat. Regret stabs me in the left palm. I can’t sit with either feeling for long.

I came home, chest burning and palm throbbing, and started scrubbing the kitchen floors, harder than necessary, and on hands and knees, getting all the corners the mop can’t reach. Only when my breathing came swift and heavy did I stand up again and toss the filthy paper towels in the trash. The floor looked good. I felt better.

The truth is, I never thought that Mom would be the first to go. Fear had made me build a life around preparing to lose Dad. Not even her terminal diagnosis could pierce the Great Lie I had been telling myself. Once, early on in her diagnosis, I had found a magazine article about Multiple Myeloma and eagerly begun to read. I felt like a dutiful daughter, a curious scholar, and had a certain “can-do” attitude when I started, like “Okay, let’s do this!” It was about a woman who had gotten the disease in her early 30s and become a massive, record-breaking fundraiser for its research. I was ready to look the symptoms dead in the eye and figure out how I could be of most help to my mom.

But when I got to the part, several columns in, about prognosis - that at 5 years it was around 50% and that none much made it past 9 - I slammed the magazine shut and shoved it from my lap. I also brutally banished the thought from my mind - to the extent that until I was finally, and truly, saying goodbye to her - on the phone, on a Tuesday night, while dinner sizzled and burned on the stove top, and Seu, only 18 months, whimpered in the background, “Why Mommy kwy?” I literally did not think that she was going to die.

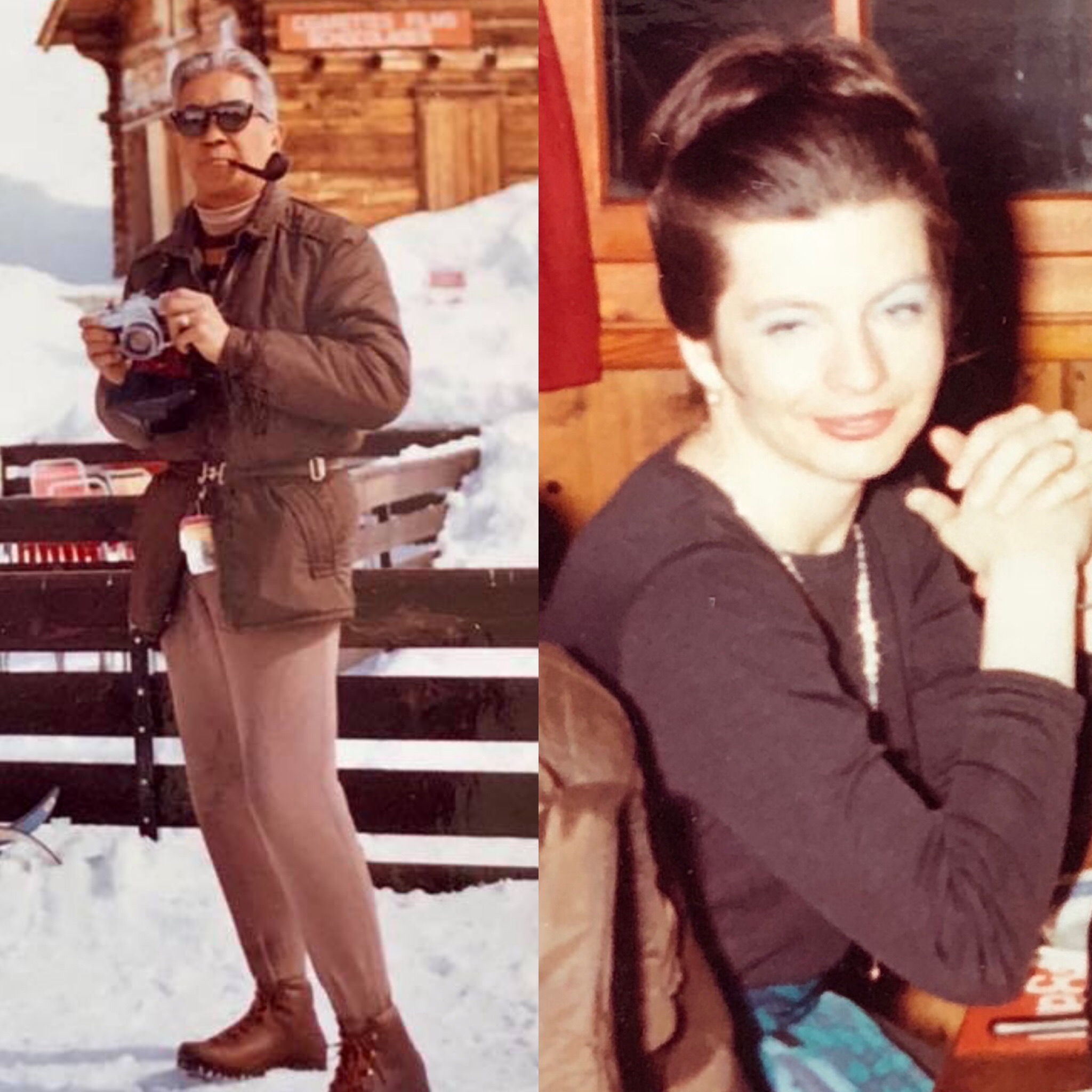

It was impossible. Who would spend the next 3-4 decades remembering and missing Dad with me? I had thought of all the ways she might fall apart after losing him, all the ways I might have to stretch myself to meet her needs as well as my own. I had thought of mother-daughter trips abroad, tearful spreading of ashes, quiet holiday times with gentle laughter over the man who had been our North Star. I imagined her walking me down the aisle to give me away, holding their first grandchildren alone, maybe getting a small apartment near me so that we could be closer. I took cues from her and how she interacted with her mother, my Grandma Wiltrude, who had been widowed ever since my Grandpa Russell, at the age of 60, had gone for a walk in the woods in Vermont and fallen to his knees on the forest floor. The poodle, Jacques, who was a clever dog, fetched help, and Grandpa made it to the hospital, but never home again, and Grandma went on without him for another 30 years.

So I had anticipated things going for Mom and me. I had anticipated it, imagined it, seen it for so long, that it had taken on the heavy weight of Prophecy. And it’s not that I wanted it that way. The fear these images put into my heart was desperate and choking. A life without Dad was the most painful, unbearable and earth-shattering thing I could imagine, but imagine it I did. I invited the thought over and over again; sat with it; needled it, pressed it; shivered with the pain of it; but was unable to stop it. I wanted to be prepared. My folly was to take for granted that Mom would be doing it with me.

To be fair, this is absolutely what my parents expected as well. They dithered at first about the wisdom of having a child at all, with Dad entering his seventh decade. What were the chances that he would even be there for my high school graduation? Not that good, actually. In 1971, when they were married, the odds were that he’d only see me through the 4th grade. But Mom wanted a baby. Now on her third marriage and with no children, this was her last chance. They both thought the rewards were worth the risk. You know, “it’s better to have loved and lost…” and all of that. I also think their happiness at having found each other and gotten another chance in life after painful disappointments just made them feel a little bit invincible. They were swimming in the optimism of new love.

And so I was born on March 9, 1973, when Mom was 32 and Dad was 59, almost the same age his father in law had been when he went leaf-peeping and never came home.

Worrywart

One of my earliest memories is of fretting about “Dad dying soon.” Mom called me “a worrywart.” On this day, probably around age 4, I lay on my back in bed with my legs perpendicular against the yellow wall, sliding them self-soothingly side to side, my Sniffy (once white, with a smooth satin trim, now mangled and in gray-ish tatters) shoved to my face. A fat tear worked its way down one temple to the bedsheets. I can feel a question lingering in the air between us. Mom sat on the edge of the bed, patted me on the stomach and told me not to be silly. But as far as I could see, the last thing I was being was silly. Everyone at the playground thought Dad was my Grandpa, and I knew that grandpas die.

Years later, I sat in the cafeteria in 5th grade, choking back tears of anticipatory regret, while my classmates howled and chucked napkins at each other, banged the tables and scarfed ding-dongs. An apple rolled inexplicably, and with purpose, past my feet. “What if Dad dies and never knows how much I loved him?” My throat was thick with the thought.

When I was 25, Brent and I decided to get married. It wasn’t a proposal. It was a practical conversation over burgers in Boston. We had been together so long at that point that I might actually have laughed if he had fallen to one knee or tried to surprise me. One of the things under consideration was how many of our loved ones were getting up in years - Brent’s grandparents and Great Aunt Dee; for me, there was GG and Grandma Wiltrude and …. I didn’t let myself think it, let alone say it. I couldn’t.

We went about having babies the same way. Mom already had her diagnosis at that point, but her death was so incomprehensible to me that it was barely a blip on the radar. I felt sure that Mom was going to be one of those people who was mysteriously able to live with terminal illness for decades. Look at Magic Johnson! She looked remarkably well, five years in, and was as active and vibrant as ever, talking about the coming Thanksgiving as much as long-term repairs to the family cabin, or future family get-togethers as if she knew she was going to be part of them. She never let her illness limit or define her; most people didn’t even know she was sick. From what I could tell, the only thing that had changed was that she had lost a bunch of weight (and looked great!) and had become diabetic due to the steroids she was on. She kept her insulin in a fanny pack whenever she came to visit us in NH and discreetly checked her blood sugar before and after her meals and that was that. She couldn’t eat the sweets she so enjoyed anymore, but that was a good thing, overall, wasn’t it?

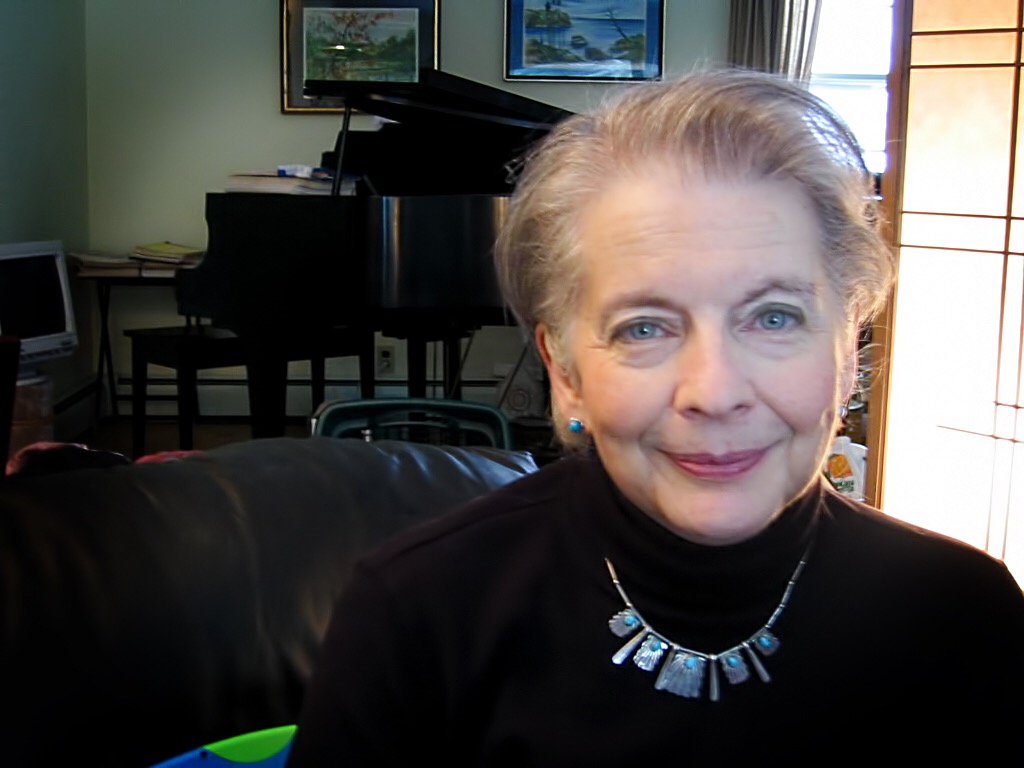

The “realest” thing about her illness to me was her hair loss, or rather, thinning. She never went completely bald. At some point, her nearly waist-length hair got so thin that she had to relent and cut it short. Although I had always thought her long hair was old-fashioned and a bit dowdy, the first time I saw her after her haircut, I saw that the wind had left her sails a bit and I felt her fear and sadness keenly. First of all, she had never had short hair and hadn’t the faintest clue how to style it. She had never had a part in her hair, and so, even short, she simply brushed it flat back off her forehead, where it ended bluntly behind her ears. Dad tried to cheer her up with humor, saying she looked like Al Sharpton. That went over about as well as you’d expect it to.

My way of cheering her up was to take her to the drugstore and go to the beauty aisle, where I helped her pick out some of my favorite and must-have hair products, including a good hair dryer and a round brush. We came home and I washed her hair in the same sink that she had bathed me in as an infant. I put in the volumizing mousse and dried her hair in the mirror, showing her how to use the brush to lift each section of hair and use the dryer hot on the roots, and then give a quick cold-shot to cool and “set” the hair. Then I gave her a part and tucked the sides behind her ears to give more of an attractive shape to the whole thing. Finally, there was hair fudge and hair spray to keep the volume.

Mom was self-conscious about her ears and wanted to pull the hair back out from behind them, which was, I thought, a decidedly terrible idea and I convinced her to live with this new ‘do for the day and see how she felt. The truth was, I couldn’t really tell how she felt. I was enthusiastic about the result and she agreed to let me take a picture. She smiled wanly for the camera, her vulnerability clear. Her ears, of all things! What on earth could be wrong with her ears? They were lovely ears, shapely and flat against her head. I felt helpless in ways I couldn’t articulate and didn’t let myself try.

Today, I am looking at this picture and letting feelings flow freely, and I think to myself: maybe tucking hair behind her ears made her feel girlish and young. Maybe the whole exercise of going to the drug store and playing with beauty products with her daughter was a lively and optimistic thing to do. And maybe, when death is in the room, girlish and lively things hurt.

This was the last time, for a very long time, that I saw any hint of fear or vulnerability in Mom. I chastise myself that I pretended for nine years that she wasn’t going to die, but the truth is that she also encouraged me in this fantasy. She didn’t want me to be her crutch or confidante. As a mother myself now, I know and empathize with the primal urge to protect your children. I think Mom made a decision early on and stuck to it. She would not let her illness impact my life or energies in any negative way if she could help it. The possibility that this might one day leave me with regrets or guilt about how it all unfolded was, I am sure, an acknowledged and accepted outcome; she had faith that I would eventually, with age, experience and wisdom be able to come to right with it.

I did sometimes see her lying on the couch in a pose of retreat, staring out the window or with a forearm flung across her eyes, while Dad sat on the edge of the cushions holding her hand gently in both of his and murmuring things to her I couldn’t hear. Of course they were talking about love and death and hope and carrying on. But I let myself imagine that she’d had some trite disappointment that day, like a silk painting project that hadn’t turned out the way she’d hoped.

In time, Mom seemed to settle in to things. Multiple Myeloma is blessedly free of severe symptoms at the outset and one can live a fairly normal life, if one chooses to. I allowed myself to continue the old pattern, then, of assuming Mom was fine, and fretting freely over the fate of Dad. The urgency I felt about having children, as I entered my early 30s and he entered his mid-90s, revolved around him.

I knew him mostly as a deeply generous, funny and fun-loving man, but he had a volcanic temper, and was also prone to fits of moroseness. A dark cloud descended on his features and you knew nothing you said at that point was going to be right. He frequently got the last word in arguments with an unceremonious, “It doesn’t matter; I’ll be dead soon anyway.”

And so it was that some of my earliest memories are of me trying to commit him to memory; he became the singular focus of my gaze from earliest childhood years until the day he died. When he spoke, I listened, willing myself to remember every story, deed, opinion, facial expression, every bit of body language. I studied him like my life depended on it. If this was all the time I was going to have with him, I had to “make it count,” and rack up memories to sustain me for a lifetime. I became his closest observer.

In college, my sophomore year, on moving-in day, I discovered I had lost some hardware for the bookshelves Dad had made me for my dorm room. I felt sick. “Oh no,” I groaned, and then mounted into a panic as I started shoving objects around violently in the box in front of me, “No. NOnononononono. Oh my god.” I sat back on my heels, hand over my mouth, then my forehead, trying to think. My brain had gone to mush. I dove back into the box. “Please god, no.” And then, finally batting the box away from me in disgust, a loud “FUCK!” Brent, who was my new boyfriend at the time, watched from the bed and told me to calm down.

“What’s the big deal?” he said.

“You don’t know my dad,” I said, and went on to make a lengthy prediction, some six or seven deeds deep of exactly what Dad would do and say when he found out, which would be any minute because he was coming back up the stairs with another load from the car even as we spoke. First I predicted an incredulous “WHAT?!” Followed by a very loud, very long SIGH. Next would come a thinning of the lips, tucked against his teeth and an eye roll as he shook his head in long-suffering disgust. Then he would raise his eyebrows high, in a great show of self-restraint, and start but not finish a question, “I thought I told y- …. Why didn’t y-….” which would dissolve into another loud exhale through the nose, nostrils flared to maximum width. “Oh boy,” he would say, in the least “oh boy!” voice you can imagine. Next could come the sound of him sucking on his front teeth. And then, finally, in a voice of ultimate resignation “Ooo-KAY-ayyyy. Alright. Welp. That’s that then. Can’t do anything about it, we’ll just have to get some more.”

When Dad clumped down the hall, carrying my Apple computer in front of him, I sneaked a sideways glance at Brent to make sure he was paying attention. Dad put the computer down and then let out a throaty exhale of satisfaction. “Ahhhh,” he said through his teeth, which were clamped around a pipe, as usual. He grinned broadly from behind his flip-up sunglasses, and stood with arms akimbo, surveying our progress. The Jolly Green Giant goes to College. I was loathe to speak.

“Dad, I’m really sorry,” I said, as brightly as I could. “It looks like I lost the hardware you got for my bookshelves….” My voice trailed off as the smiling face fell and the whole pageantry unfolded, exactly, and I do mean, exactly as I had foretold. The only part I missed was Dad’s low-key confusion over why his daughter’s boyfriend (whom he called “the big guy”) would be rolling around on the bed in tears of laughter the longer he talked. Dad kept jerking his eyes to the bed as he went through his list of antics because Brent was positively yelping. He had to wipe his face repeatedly after that incident. He still talks about it to this day. “I was crying,” he says, “CRYING!!! And your dad couldn’t figure out why!” Point is: I. KNEW. MY. DAD.

Dad was, in many ways, the center of my universe, and not just because I had spent a lifetime thinking he was going to die any minute. His charisma was abundant and overflowing; he was seductive in all senses of the word; and he was uniquely gifted with children. I have compared him on this blog to Greek gods and beer commercials. How many people can you say that about? Importantly, he was also my primary caregiver, from preschool on, as Mom forged ahead - one among the first generation of truly professional career women in this country. She was a computer systems analyst at Kodak. Dad became a stay-at-home dad at 65, about the time I entered kindergarten.

So it was he who taught me to tie my shoes; the difference between “who” and “whom,” “I” and “me,” “a” and “an,” and why I should care; he who took me out fairy-hunting in dew-covered mornings; he who brought me to the Rochester Museum & Science Center on Friday afternoons. My black patent-leather Mary Janes clicked satisfyingly on the marble floors as we strode, hand-in-hand, to the reception desk, ready to see dinosaur bones and Indian dioramas, every week as exciting as if it were the first time. Come snack time, my eyes crinkled at him over my special treat in the red-and-white checkered café - a Twinkie for me, coffee-and-cream-no-sugar and a plain donut for him. It was also he who woke me up early on certain mornings so I could watch Captain Kangaroo, and he who spun elaborate tales for me at night, when Mom had fallen into an exhausted stupor after dinner.

My favorite tales were what he called “The 39 Kids.” They were all about me, magically shrunk to about 6 inches in height, sneaking in to the science museum after dark and getting into all kinds of hijinks. The “39 kids” referred to all of the friends I added to the stories as we went along. Before every telling, we had to spout off the list of 39 kids who were going to be joining me on that night’s shenanigans. It started with my niece, Stacey - Dad and Gretchen’s granddaughter, who was the same age as me and my best friend - then grew to include a number of kids from school, and finally, even Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck were in on the adventure, as were the chipmunks, Chip and Dale, and Porky Pig and Yosemite Sam. Naturally, Dad did all the voices.

I remember one story in which he had me tease the night watchman from inside the jaws of the T-rex skeleton over his head. The watchman spun around with his utility flashlight and yelled, “Huh? What was that? Who’s there? Who said that?”

“Nobody!” Dad had me call down from behind a dinosaur incisor, before sending me sliding down the skeleton’s spine to make a fast get-away off the tip of the tail. How I screeched and rolled with laughter. Yes, Dad even invented the story of “Night at the Museum,” 30 years before that movie was ever made. Is anyone even surprised at this point?

Well, what you have read so far captures, more or less, my entire thought process that day that I violently scrubbed the kitchen floor asking myself, “Why don’t I talk about Mom more? Have I ‘erased’ her in the eyes of others? Why couldn’t I have been the daughter I was for Dad, for her???”

Denial

Most people tend to think of “denial” in pejorative terms - it seems cowardly, childish. But my friend, Christine, who is a prominent psychologist, said one day, “You know, denial can also be a really good thing - necessary even - in times of upheaval. It’s a protective strategy and actually eases people’s passage through painful transitions.” This was news to me, and welcome.

I had been in denial about Mom’s condition since I started reading that article on Multiple Myeloma all those years before - nigh on a decade. In the interim, I had thrown myself into establishing a life and career for myself. I finished my Ph.D. in Historical Archaeology at Boston University. I took a prestigious visiting professor position in the Vassar College Anthropology Department. I wrote my first book, on the archaeology of Northern slavery, based on my years of excavation at the Isaac Royall House, in Medford, MA. I presented at national conferences and published peer-reviewed articles. I also eventually left academia to “enter industry” as an archaeological consultant. In all this time, I did not exert myself to call her more than usual, or make any effort to go home to visit more often. When I did go home, I found myself easily regressing as I always did into adolescence.

“What’s for dinner, Mom?” I asked, even noticing that there was a stool in the kitchen now, where she could sit when she got too tired to stand.

As the illness progressed, the suspension of disbelief became harder to maintain. Dad spoke freely and humorously about Mom’s “fancy pants,” which were for her newfound incontinence. She chuckled flirtatiously back at him, “oh, you!”

I, in denial, cringed and tried to unhear it while Dad went about the much more important work of making sure Mom knew she was still worthy, still loved, still beautiful in his eyes.

Listen, watching my parents flirt over adult diapers is just about the most loving thing I’ve ever witnessed, but it scared me and made me look away or head to the kitchen for a snack.

When Jin was born, I was so overwhelmed by new parenthood myself, that I found visits home exasperating. The house was the opposite of child-proofed, and Mom was careening toward a hoarding problem. Once, when Jin was cruising, I put him down in the house and went back out to the car to get some of the luggage. By the time I returned, moments later, there was my child teetering wildly through the dining room with two unsheathed hypodermic needles in one hand and a sword-shaped letter opener in the other, heading straight for a vacuum cleaner whose cord was uncoiled across the floor in great undulating loops just looking for a foot to grab. The bathrooms were filthy and dishes filled the sink. There were only two places to sit in the entire house, and the whole place smelled like cat pee. I frenziedly bleached the bathroom, mouth turned sharply down at the corners and chin tucked back against my throat. I checked the late hour and thought of the 8 hour drive just behind us and the sleepless night with an infant ahead of us, and I judged Mom for being a terrible housekeeper.

The Unraveling

When Jin turned one, Mom and Dad made what would be their last trip to NH to be at the party and to see our new house for the first time. My childhood home was beginning to feel like Death’s waiting room, but here, in my own (new) space, I felt free to enjoy my parents’ company. I remember Mom plopping on the couch next to me one morning, the cushions warm from the sunshine, and stretching her legs out and arms up, and fairly purring “Mmmmmm, this place feels so good, Sweetie” reaching a hand out to pat my thigh. Jin stood on the other couch in the room with arms clamped stiffly at his side and waited for Dad to say “tim-berrrrrrrrrrr!” before falling backwards into the cushions. He gave deep, bubbling belly laughs, and scrambled back into position. “Again, Bop-Bop,” he said. That was Bop-Bop for “Grandpa Bob.” Grandma Karen was “Bop-Bop Kayn.”

I was proud of the life we were building, and so happy to have them there.. Despite my lifetime of worry, in fact, both my parents were able to know and fiercely love my kids, and to see me, too, inhabit the role of “Mom” in my own right. Mom told me repeatedly that it was “so neat” to see.

Dad dissected a hundred-year-old doorknob that visit and figured out how to fix it. He also fretted and plotted for days over how best to jerry-rig a perennially running toilet. The toilet, in fact, became his Moby Dick that week. He actually lost sleep over it, and I found him in there morning, noon, and midnight trying his new ideas. He gave his daily reports over breakfast. Engineering problems to be solved were his specialty. They were dragons to be slain and they made him come alive.

Jin’s party was large and lively and Mom and Dad were popular guests. I went to sleep on a cloud of well-being.

(note: if you are on mobile, turn the phone sideways to see the captions for the slideshow below)

The next morning, I awoke to muffled shouting from the guest room downstairs.

“HOLD ON TO ME KAREN! I can’t LIFT YOU!” Dad was saying.

“I told you, I CAN’T, BOB!” Mom cried tearfully.

Brent and I bumbled sleepily down the stairs. Brent knocked and entered without waiting. Mom was in bed and had awoken to find that she needed to go to the bathroom, but she couldn’t move her legs. Dad was in a fuzzy robe that was pulled open to the waist, revealing his emaciated frame. You could easily forget, spending time with him, that Dad was 95 years old, but seeing him half-naked made you remember.

Brent got one arm under Mom and got her to the bathroom, helped situate her on the toilet, and left to give her privacy. We three - Dad, Brent and I - stood anxiously outside the closed bathroom door, waiting for her to be done. We took turns leaning in to listen.

“Are you done, Mom?” I asked.

“Yes,” came a small voice.

“Do you need help?”

“No!” she cried.

“I’m calling 911,” I said.

“NO!” she yelled. “Don’t!!”

By the time the ambulance arrived, she had still not come out. Nor would she let the EMTs in the door.

“You have to go to the hospital, Mom,” I called through the door, using my new-parent voice, “This is non-negotiable. The ambulance is here. We need to find out what’s going on.” Silence. I looked at Brent helplessly and began to cry. “I can’t go in there, Brent” I said in a choked whisper. “I can’t go in there.”

Brent, always stalwart in crisis, saw my face and took command of the situation. He knocked on the door and said kindly, “Karen? It’s Brent. I’m coming in to help you, okay?”

After a short silence, came her weepy voice again, “Okay.” She trusted Brent. She loved him. He went in with the professionalism of a nurse. Mom was stuck on the toilet and couldn’t move. And that is the day my husband wiped my mother’s behind without hesitation, comment, or complaint. “So this is what ‘for better or for worse’ really means,” I remember thinking.

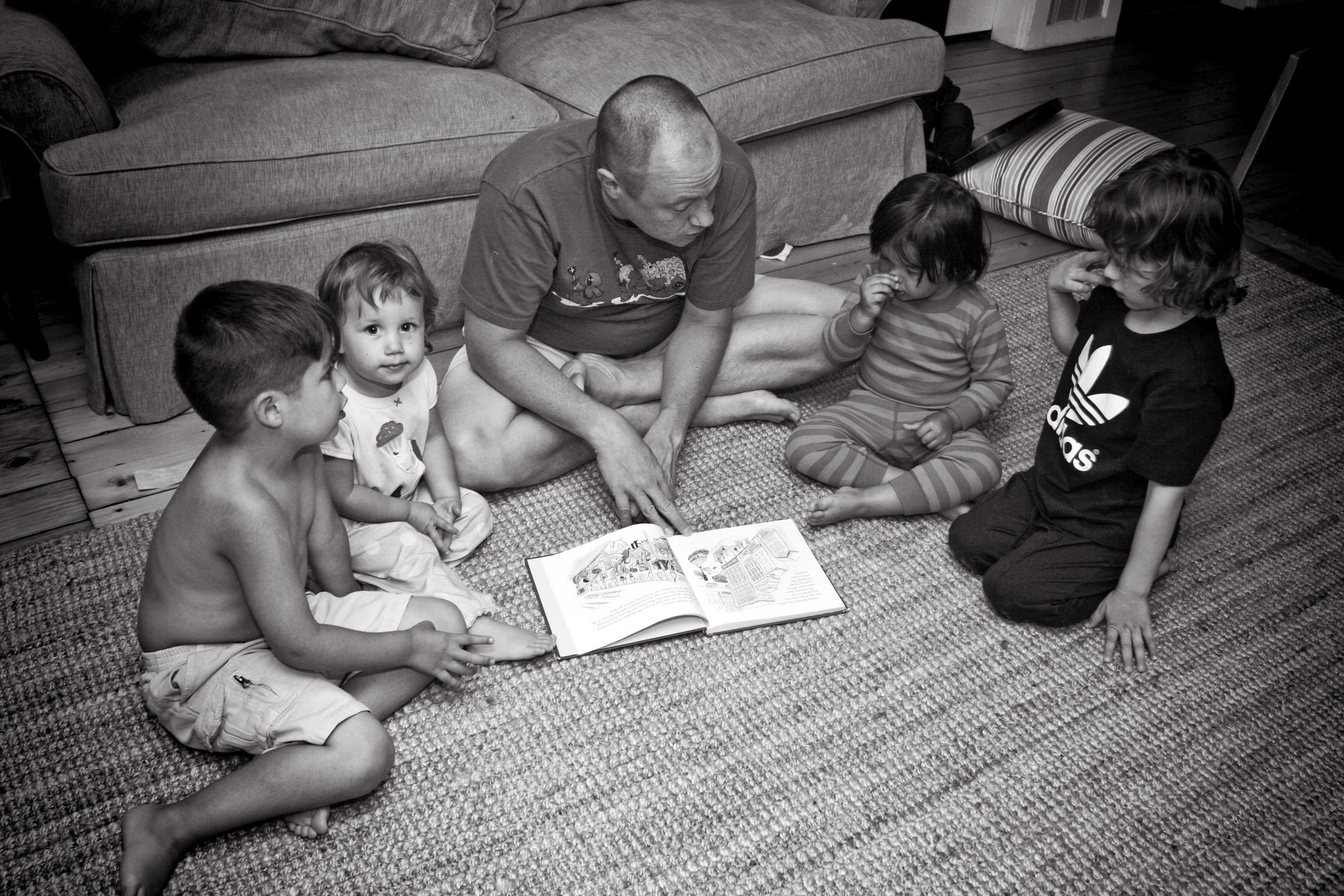

When he brought her out, she was clean, clothed and had her dignity intact. The EMTs took over from there and brought her to Wentworth-Douglass. While Dad and I talked to doctors, Brent took Jin, who was getting restless and whiny, to the family room there and spread some puzzles and blocks on the floor for him. At some point during that evening, Dad and I found ourselves in the hall, looking through the window at Brent on the floor with one-year-old Jin.

“My god, Honey,” said Dad with quavering voice. “He’s completely selfless, you know?” I leaned my head on his shoulder and nodded silently. “I mean, completely….”

(note: if you are on mobile, turn the phone sideways to see the captions for the slideshow below)

Mom had several tumors growing on her spinal cord, which were causing the partial paralysis. With years of PT, she did regain some mobility, but she couldn’t drive anymore and never walked unassisted again. Her hands were also clumsy and she couldn’t paint silk anymore.

That first night in the hospital, I sat on the edge of her bed, held one of her hands in mine and rested the other on her stomach, as she had so often done with me, and said what six years of denial had never let me say before. “I’m sorry, Mom.” I hoped she knew how much bigger the feeling was than the words I was able to get out. Sorry just didn’t even come close.

She teared up, nodded, and said, “I know. I’m sorry too, Sweetie.”

She stayed in the hospital in NH for a month until taking an 8-hour, $11,000 ambulance ride back to NY. With this episode behind us, Mom lived for another three years of “new normal.”

Mothers Don’t Die

Let me tell you about the last weekend we spent together, which also happened to be the last weekend of her life.

Mom went out on a high note, on the most beautiful, breezy, sun-drenched summer’s day of the year, which then yielded to a clear night unusually full of stars. By some profound and graceful turn of fate, Brent and I and the boys (now four and 18 months) were able to spend five of Mom’s last seven days on earth with her, unburdened by any knowledge of what was to come, and doing the things that she loved best - talking about love, life, art and politics; going to the Main St. festival in my hometown; pancake breakfast with the boys; going out for good Chinese on Saturday night, where my brother, Rob, locked the keys in the car.

Mom stood outside the China Garden, leaning against her walker in the parking lot, while Rob, Brent and I scurried in circles around the car trying to figure out how to get the door open. We were in a fix! As the seconds turned to minutes, I seemed to feel the weakness in Mom’s legs behind me and began to fear she might fall over. I looked back and saw Dad, too, leaning heavily on a cane. My mind whirled through possibilities - get them back inside, find a seat, call AAA …. Just then, the proprietor of a small wine and liquor store next door, came outside and locked his doors, rattling the handles to check them. He turned around, noticed the commotion and came to find out what was happening. Seeing the pickle we were in, and the odd angles at which my parents were standing, he ran to his car, ransacked the trunk, and came jogging back with a wire coat hanger held up in one hand.

“I’ve had this thing in my car for 20 years,” he said, triumphantly. “Never had to use it till now! My kids think I’m crazy.” Keeping it in the trunk meant that he had it in there to help others, not himself, I realized. Who imagines that he might one day have to help someone break into their own car? And then keeps this fantasy alive for 20 years, through multiple vehicles, and all evidence to the contrary? And why was this the guy we encountered in an empty parking lot when we were in exactly the kind of sticky spot that he was equipped to handle? I felt the buzz of Big Magic going on.

The man quickly untwisted the hanger, leaving a hook on one end, and slid the wire between the passenger-side window and the stripping at its base. It only took a couple of tries to get the door open. Rob hopped in the driver’s seat and zipped the car around in a wide curve, almost screeching to a stop in front of Mom and Dad. We were rescued and the liquor store owner had a 20-year quirk vindicated. And you know something? I bet we are both still telling the story. ”Who’s laughing now?” he might be saying to a naysayer of coat hangers in the car. How wonderful.

Mom was full of vim and vigor on this visit, something that I didn’t question in the moment because it was wonderful and I wanted to enjoy it. In hindsight, though, it does seem to me that this was the great burst that signals a dying star. I think there was something deep inside of her that motivated her to really make this one count.

When we first walked in to the house on Tuesday night, she straightened herself up eagerly on the couch, eyes bright and sparkling, with a delighted smile. I noticed her cheeks were plump and pink and pretty as could be as she took us all, one by one, into her arms from her seated position.

“Wow, you look so great, Mom,” I said. My heart fluttered with optimism.

She was so excited that her body seemed to vibrate with it. Thereafter, she was up and dressed and downstairs, ready to go by 8 or 8:30am every day, delighting in the boys’ antics, which were many, and played out at her feet. The visit was rich and full, the best I can remember.

On Sunday afternoon, we hugged on the couch and she told me she’d see me at Thanksgiving. We made the long drive back to Portsmouth with stormy skies overhead, and at one point drove right into a full double rainbow that arched across the sky, straddling the whole of I-90. It was my first double rainbow, and it was big and bright. Mom loved rainbows. She had rainbow stickers on her kitchen windows; she put rainbow patches on my childhood clothes wherever I wore holes in them; she bought rainbow sheets for my sister’s and my beds; and when the kids were born, she sent “rainbow makers” to hang in the nursery windows - faceted crystals hanging from a small motor that spun the crystals and cast tiny rainbows all over the room. She was, you could say, a rainbow enthusiast. I tried to take a picture of the phenomenon over I-90 but it was so wide and so high that I couldn’t get it into the frame. I figured I would just have to tell her about it in as rich detail as possible next time we talked - sometime next week.

And then…on Tuesday, she died. Brent had had to fly immediately to California the day before, so I was alone. I had picked up Jin and Seu at preschool and had them on the floor outside the kitchen while I began to cook. Seu began to whimper about wanting his “mowk” (milk) but before I could get it, the phone rang. It was my sister-in-law, Susie. She said Mom had gone to the hospital that day in a fever and having trouble breathing. I took that in for a moment, trying to reconcile it with what I had seen just 36 hours before.

“She’s lost consciousness, Alexka,” Susie continued, “and her organs are shutting down. Your dad is here, Rob and I are here. She’s peaceful, she’s quiet. She’s not in any pain.” She hesitated a moment and said, “It looks like she’s not going to make it through the night.”

“Tonight?” I asked. I exhaled through pursed lips the way I had learned to do in childbirth classes. “Okay… Wow. Um.” My mind was screaming and empty at the same time. Seu whimpered more loudly about “SNACK.”

“I thought you might like to say something to her on the phone.”

“Can she hear me?” I asked, stalling.

“I don’t know. They do say that hearing is the last sense to go. I’m going to hold the phone up to her ear now, okay?”

And so I started talking into a silent telephone. My mind reeled and flailed but my heart found the words for me. Finally, I could think of nothing else to say but, “I’m going to miss you so much, Mom. I love you. Goodbye.” Afterwards, as I made phone calls to other family members, pacing wildly from room to room, I heard Jin, who was only 4, get a stool from the bathroom and go into the kitchen and open the fridge.

Whereas this was normally the time of day I could count on him to bedevil and frustrate his baby brother, today he got out the jug of milk by himself, which he had never done, and a sippy cup; he filled the cup, screwed the top back on and brought it back to Seu, and with a small bowl of cheerios no less. Seu, who had been crying because he wanted his after-school snack, took the cup and cheerios and quieted down, but then started worrying about “why Mommy kwy?”

While I listened to my uncle losing his composure on the other end of the line in my right ear, I heard Jin with my left:

“Seu. It’s okay. It’s okay. Mommy is just sad because she’s losing her mommy tonight. Grandma Karen is dying.” I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. He went on, his voice getting more animated as he spoke, “But Seu, it’s going to be okay because guess what, Grandma Karen is going to go live up in the sky and become a big, bright, shiny star, and then we can all make a WISH!”

“I ahna mek a ish,” said Seu, intrigued.

I turned over my shoulder and looked at them. Jin sat back on his heels and looked up at the ceiling, shaking his head wistfully. “I can’t wait to see that star.”

This was Jin’s own unique interpretation of death. We had never talked about it in these, or really any other, terms. I was amazed. What made him think she would go into the sky and become a star to wish upon? When I tucked him in that night, I told him I thought he had saved me that day. “Yeah,” he said, squirming with pleasure, “I saved you.”

I didn’t sleep that night until the wee small hours. I searched through my phone’s voicemail trash on a hunch. There, buried deep within, was a voicemail from Mom. Left several months earlier, it happened to be another Tuesday night, and another 8:00 hour, and the words seemed like something she would have said to me again, on this night, too, if she could have. And so, in a way, I felt they really were her final words to me.

At the memorial, which took place some three weeks later, I learned many things about Mom that I had had no idea about. How did I not know that she had qualified for the 1976 Olympics in fencing, but didn’t go “because it was too expensive” (and, presumably, because she had three-year-old me at home to take care of?)? How did I not know that? Why didn’t she ever say anything about it? And why had I never asked? I knew she had fenced in college and I remember going to the gym with her and watching her “swordfights” but Olympic level? Amazing. Another woman told the story of how she and Mom went on a cross-country road trip and got to laughing so hard in Texas one day that they literally had to pull to the side of the road until they could see through their tears again. MOM went on ROADTRIPS? Other people stood and talked of her almost as their personal Angel of Mercy. Even her physical therapists were there and felt compelled to talk about her amazing gumption and attitude and good humor since she had fallen ill again in NH. People like her were the reason they did what they did. Her reach was broad, I realized. Her touch, loving and light.

I also reflected on her resilience that day. Not everyone can bend without snapping. I had learned so very much from Mom's quiet grace and strength in the face of relentless adversity, about how to deal with this, my own hardship in losing her. This was her gift to me. I found myself trying to face forward and outward. Like Mom always did.

Even so, I couldn’t speak her name or hear her voice for a year after she died. I listened to that voicemail one time and put it away. In truth, I couldn’t even let myself think about her, which became its own source of pain for me. “She doesn’t deserve that,” I kept saying.

A Gathering

The following August, Michael and his family flew in from Oregon; Stacey and hers came up from Connecticut; Rob and Susie drove Dad from NY; and we all met at a lake house in Vermont to celebrate Dad’s 99th birthday and to remember Mom on the first anniversary of her death. It was a healing time and a bittersweet one. Mom lived for family and I felt keenly that she was missing out on this big time. It was also hard to see Dad so old and alone. On the other hand, I couldn’t remember the last time all of the families were together in one place, and it was a great opportunity for the grandchildren and great grandchildren to get to know each other again, for Dad to survey his legacy. There was a lot of laughter.

On the 23rd, which was the day that Mom had died the previous year, I stood out in the front yard, which served as a promontory overlooking the lake and watched Brent and Jin sitting on a floating platform far out toward the middle. Seu came trundling out behind me with a pair of binoculars and wanted to “see Jin.” He was too small to paddle kick the inner tube out there with the others. I was filled with a sense of well-being.

For the first time in a year, I let my thoughts fall and rest on Mom. And I spoke to her in my mind. “Was there ever a person who deserved a beautiful send off more than you?” I asked. “I think that you won that prize fair and square, Mom, and deserved it more than anyone I can think of. Dad turned 99, you know, and we’ve had such a beautiful week. I’m so sorry you aren’t here to see it. It’s the first time I can feel that we are all going to be okay. I know that we’ll continue to lead rich, rewarding and productive lives - living, loving, laughing, doing… It just won’t be the same without you.”

Jin’s voice yanked me from my reverie. “MOMMY!!!!!” he echoed across the surface of the lake, his voice ricocheting from hillside to hillside and back to me. My eyes snapped to where he was, standing in bare feet and an oversized life jacket, with one arm pointing out in front of him. “LOOOOOK!!!!! A RAINBOW!!!”

A chill ran down my spine and out to all of my extremities. There, indeed, was not just one rainbow but two - a full double rainbow - brighter and more vivid and closer than I had ever seen or imagined possible. It had appeared out of nowhere, in the blink of an eye, and it looked almost close enough to touch. The only other double rainbow I had ever seen was the one I saw the year before, on the last day I had seen Mom. I regretted never getting the chance to tell her about it because she had died so suddenly after our departure.

Even more remarkable: both arcs actually landed in the water a few yards from the platform where Jin was hopping around screaming in wonder. Brent and Jin were quite literally sitting at the end of a rainbow. I, for one, hadn’t known that a rainbow’s end was a real thing. I thought the physics of rainbows probably just made that an imaginary exercise. But here we were. The lake, the lake house, our family, I - we were at the literal end of a rainbow. I was standing in my own pot of gold.

(note: if you are on mobile, turn the phone sideways to see the captions for the slideshow below)

I tried to take a picture but the rainbow was too close; I could barely get a chunk of one arc into the frame. I needed my wide-angle lens. I weighed the costs and benefits of sprinting to get it, or staying rooted to the spot to soak in the wonder for as long as it would last. I chose the latter.

Integration

The lake house trip felt like the beginning of an “integration ceremony” for me - demonstrating for the Universe my commitment and budding ability to integrate Mom’s loss into a life that had new and unexpected outlines. I felt I was crossing a threshold and when I got home I continued the “ceremony” by facing my year-long avoidance of her memory head on. I made a memorial video for Mom, using the voicemail “she had left me” on the night she died (embedded below). I also took out the plastic grocery bag bulging with pictures of her that I had gathered the year before, but never been able to look at until now. I spent the next several nights carefully curating a photo album where she now resides in rich and multi-faceted glory: big sister, affectionate daughter, brilliant scholar, career woman, textile weaver, silk painter, world traveler, personal boundary pusher, loving wife, doting mother, enthusiastic grandmother, cheerful in sickness and in health.

While I worked on that photo album, I ended up answering some of my own questions. Why couldn’t I have been the daughter I was for dad, for her? Well that’s easy, I thought. Because I wasn’t that person yet, that’s why. Losing Mom was the fire that tempered my soul for that job. It toughened and strengthened me to step into the much more challenging role I would have to inhabit to see Dad to the end of his life. There is simply no way I could have ensured that Dad had the end-of-life he deserved if I were still the girl who couldn’t go into the bathroom to help my own mom when she was stuck on the toilet.

In a way, then, Dad’s final years, my new-found ability to aggressively intervene on his behalf, and advocate for his needs, and see them through, and the relationship that blossomed between us in that time, was Mom’s final gift to us both. “Thank you, Mom” I whispered at one of the photo album pages open before me. “I could never have faced this alone without you.”

When I finished the album, I poured myself a glass of wine and flipped the book to the beginning to go through it page by page. Somewhere in the middle, I stumbled upon a pearl of wisdom for myself: Mothers don’t die. And I don’t mean that in a Hallmark platitude kind of way, I mean it literally. I thought to myself, looking at the pictures and recalling the old memories, “Jeez, I don’t feel like she’s gone when I’m looking at these. She feels alive.”

This triggered a whole new set of questions, answers, and revelations. A small voice piped up in my head. “She feels alive in these pictures. Okaaaay...” it said, seemingly trying to draw me toward further logical conclusions. “Where is she still alive?” it asked.

In my mind, I answered.

“And before she died?” the voice continued, “Where was she alive for you then?”

In my mind, I answered, my heart beginning to open.

“Did anything change between then and now?” the voice asked. “I mean really. Has anything changed? At all? Besides you telling yourself two different stories - ‘my mother is alive,’ ‘my mother is dead’?”

No, nothing has changed. I accessed her in my memories then, I access her in my memories now.

“Good,” said the voice. “And doesn’t that really mean that Mom lives in the place she has always lived? And you haven’t lost a thing?”

Disclaimer: many years later, and shortly after Dad’s own death, I stumbled upon a video on “The Work” by Byron Katie. It was called, almost unbelievably, “Fathers Don’t Die.” In it, she takes an audience member, almost verbatim, through the conversation I had with myself over Mom’s photo album in 2012. If you watch it, you will wonder how it is possible that two such similar conversations could have been independently carried on, years and miles apart. Once again, I felt the buzz of Big Magic going on. Can you feel it too?

Like, Comment, Share!

Although the buttons below work, Squarespace is currently struggling with a bug that erases the tracking at random. Please don’t let low or no numbers shown deter you. Likes and shares still help boost my visibility, even if the numbers don’t stick around to show it. Thank you!