The Gift

I don’t have much of a green thumb, but it is probably an overstatement to simply say that I “kill plants.” My attempts at gardening, which are relatively new, have been ruled by trial and error, with a little extra emphasis on error. One of my main obstacles was always that I was incapable of accepting things for what they were. So you might have stopped by one day a few years ago and found me defiantly planting irises and tulips against their nature, in the shade, because that was where I could see and enjoy them. Predictably, they would cling valiantly to life for a season, and not return. Ironically, I used to seek out perennials because I believed in investing in things that offered longtime happiness. I guess I just figured that “investment” ended at the cash register.

Growing grass was also a problem, although I had less of a direct hand in this. We bought our house when Jin was 6 months old - a place that we could grow in to. It is a lovely place - a two-story condo in a beautiful Victorian, situated on a corner lot just outside of downtown. There is just enough land to play with, but nothing like those suburban nightmares - vestiges of an 18th-century mentality, whereby Americans, who were without an aristocracy, sought to mimic one by adopting the aesthetic of a “landed gentry." Yes, did you know? The McMansion and suburban “lawn” harkens back to a time when American parvenus who wanted “a country estate” bought too much house and vast expanses of land to leave them flamboyantly idle, showing the world that they were rich enough to own land and not actually work it. Today, such symbolism has lost much of its power and it usually just means that couples are spending inexcusable numbers of weekends at Home Depot trying to figure out how to keep the dandelions and crab grass out and fix the pee stains so that the neighbors won’t frown.

By contrast, we have a quaint urban lot of manageable size. You could toss a stone from one side to the other. Mature century-old landscaping and a tall, tastefully built fence have enclosed the back of the lot into what almost feels like a secret garden.

When we bought the place, it was anything but. The lot is bounded on two sides by rows of gargantuan hemlocks that rise straight and sturdy into the stratosphere but seem almost made of rubber when the wind blows. The needles come down like rain and pile up and drift against walls, fence lines, and patio furniture. The previous owner had let the hemlocks grow unruly. When the real estate agent first walked us into the back yard through the gate, hemlock branches drooped mournfully to the ground, interlocking with each other in a tangle, scraping the dirt some 20-30 feet from the base of the trunks, and nearly reaching the back wall of the house. Nothing grew beneath these branches, which sunlight could scarce penetrate. The entire back yard was a patch of dirt. We spent our first summer in the house cutting the branches back to let the sun in and reveal the land beneath. We also immediately started trying to grow things - grass, first and foremost. We found, however, that even with the lower branches gone, the hemlocks themselves were a barrier to the sun for most of the day. We also did not consider the root system that six trees of such size must have and how much water and nutrients such a system must take from the soil.

For many years, I tilled the yard by hand with “the spiky roller thing” and spread seed, fertilized, limed, and watered the land in an attempt to have a little patch of grass to call our own. Every year, shoots would grow and then fill in, only to die off immediately the first time we left town for longer than four days. I tried all the different seeds on the market - for sun, for shade, for sun and shade - including the ones “as seen on TV” that claim to allow you to grow turf anywhere, even on a cement block. Apparently, my yard is less fertile than cement.

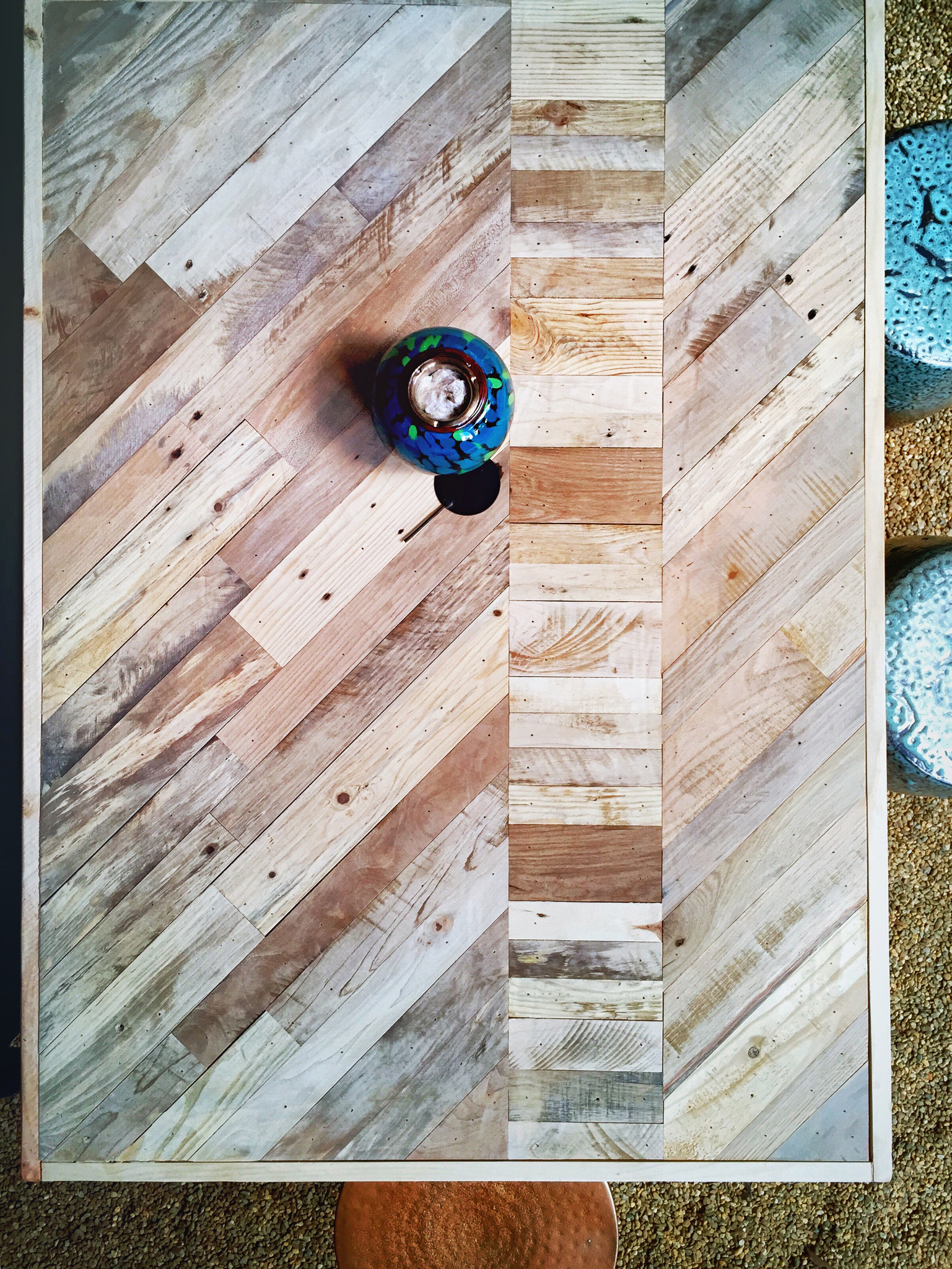

(note: if you are on mobile, turn the phone horizontal to see the captions for the slides below).

Then came two consecutive years where we paid a landscaping company to completely re-sod the area - a father and son who sweat and strained to strip the land, bring in new soil, even it out, and then roll out a beautiful green carpet for us that lasted exactly 6 weeks.

It was fun to see a father starting the task of passing on the family business and all of its knowledge to his son. He spoke low and encouragingly, demonstrating the proper angle to shave existing sod off the earth without getting caught on roots. I only watched through the window, but I knew what he was doing because I had done the same thing myself on countless occasions, training the seasonal hires (known in the archaeology business as “shovel bums”), on proper field techniques. We were often required to remove sod from private property that was being impacted by some project or another, excavate the area, and then fill it back in, replacing the sod at the end as if we had never been there.

Yes, the father and son landscaping crew did a beautiful job. But our land had other ideas.

On the third year came the guy with the hydroseed blower. In his truck was a tank where seed, water, fertilizer, fiber mulch, and lime were blended together and then sprayed out of a hose he held under one arm like a man bringing a python to heel. It took all of 15 minutes to cover the whole back lot in an unnatural shade of green that, nevertheless, left me feeling the most optimistic yet. That grass lasted until September.

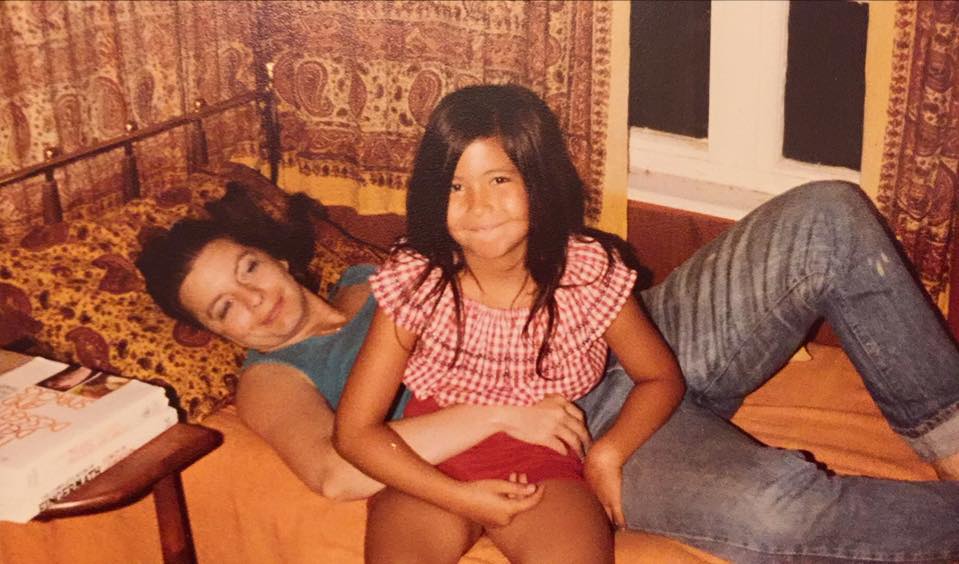

So it had been eight years. In the time I had been trying to grow a lawn and garden in back, Jin had gone from sitting in diapers in a Bumbo chair, waving his arms like a hula girl in the way that babies do and squawking like a dinosaur hatchling, to walking a mile to school in third grade, going on about the size of Jupiter and other “weird but true” facts. He also now had a little brother, Seu, who was himself entering kindergarten! How time flies.

(Note: if you are on mobile, turn the phone sideways to see the captions).

It was 2015, and for the first time, I found myself conceding defeat on the garden, disgust and despair angling for primacy. I was also, by this time, quite sure that we were entering Dad’s final year, so I had other things on my mind than grass-related fuckery and flowers who just wouldn’t throw me a bone. I felt as barren as the land I walked on.

But then I discovered meditation. Or should I say, re-discovered it?

A Seed is Planted

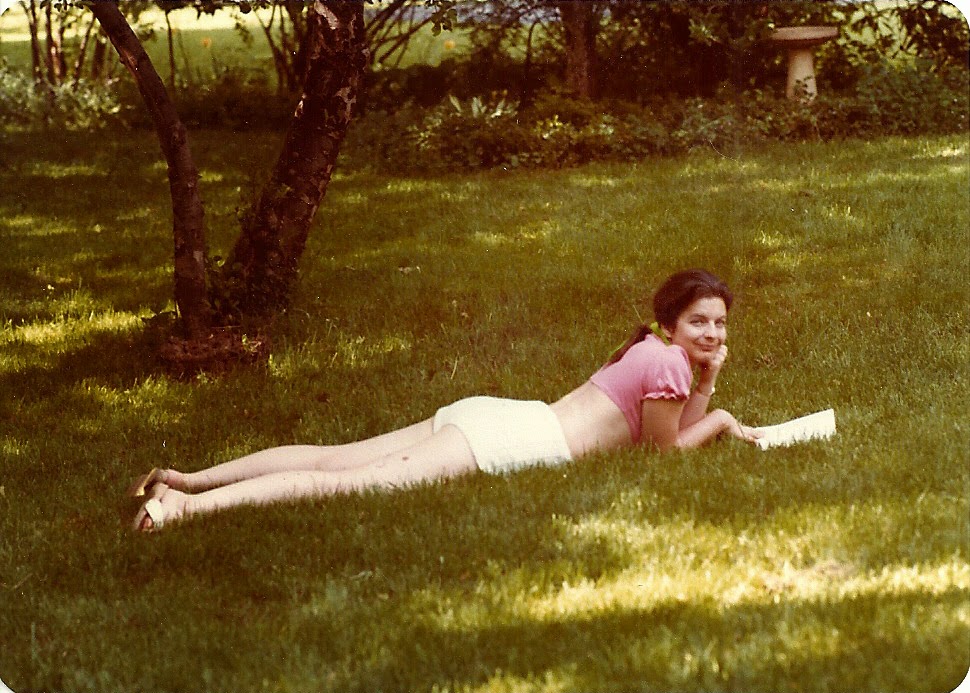

I have a memory, from many years ago, of lying on my back with my head in Mom's lap. She had cradled it with one hand and was touching my temple and pulling the tips of her fingers through the long strands of my hair with the other. Her voice was low and soft, which it was anyway, to the chagrin of my father, who was going deaf after surviving both the War and a case of the bends during a SCUBA-diving expedition in the 1960s that broke both his eardrums. The way she often used to speak into her hand, and sometimes even turn her face to the side, could make it difficult for even normal-hearing people to make out what she was saying. Upon first meeting, you might be forgiven for thinking she didn't have much to say. But you'd be wrong.

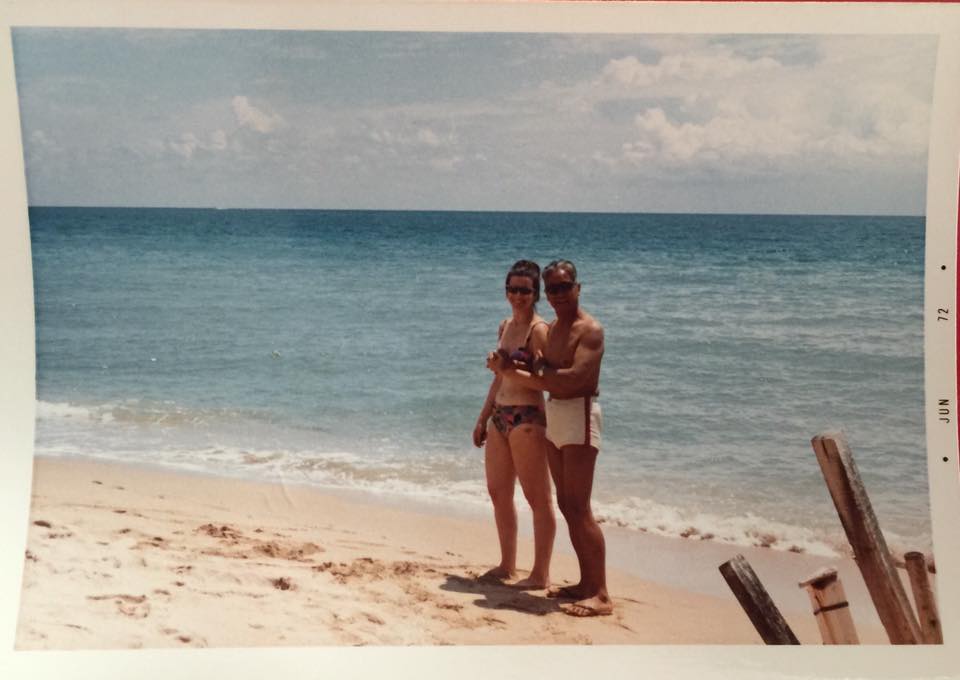

Mom and Dad met in Rochester, NY, where Dad was employed at Kodak as an optical engineer, and continued in the Army Reserve as Colonel. He had been there since shortly after World War II, with wife, Gretchen, and son, Robert Earl, Jr.

Mom - Karen Elizabeth Smith - was married to a man named John Vaden at that time. Although she was still in her mid-twenties, John was her second husband, and it seemed that key patterns were repeating themselves. Both John and Mom's first husband were alcoholics - the kind that eventually do, and did, drink themselves to death. When Mom came to Rochester in 1964, however, this was not yet clear.

In an "autobiography" that Dad wrote, ca. 1980, for the adoption application he and Mom were filling out for my sister, MeeRa, he described the early relationship so:

"John was a second lieutenant in my Army Reserve unit. He found out that I was taking my dinner at a restaurant on meeting night, and invited me to have dinner with him and Karen on those nights. Karen, very hospitable, encouraged it, and we became fast friends. The atmosphere of their apartment and the conversation were without equal in any group, and not for many months did I discern John’s problem with alcohol. For two years I tried in vain to help – joyous when John checked in to the hospital, saddened when he checked himself out again. I don’t know when Karen and I discovered that marriage was in the works for us. I do know that three years after my divorce [in 1968] we were married in Rochester, NY."

She was 29 and he was 56.

To me, he related that the first time he had seen John and Mom at the restaurant, John was holding up a large newspaper. Mom, facing a wall of newsprint, ate her meal in a silence that cut through the ceramic and glass clatter of the diner and drew the attention of the Colonel across the room. Dad wondered that night in passing, "what kind of man has a woman like that and lets her eat alone?"

My parents tempered each other in all the most important ways. "Ours is not an ordinary marriage," Dad wrote in the adoption application, "but then, we are not ordinary people." She helped to tame the dragon inside him - a creature both magical and fearsome. He helped her to reclaim her power, giving her the confidence to clear her throat and speak, in ways both big and small, literal and figurative.

In time she did become someone with great personal - if soft - power in her life, with quick and brilliant mind machinations that, I am sorry to say, our society still typically attributes to men. They allowed her to succeed in a man's world of business as a Kodak executive in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. After Dad retired, she stepped with grace and aplomb into the role of primary bread-winner, and we none of us ever wanted for anything. Meanwhile her capacity for love - spreading it freely but then finding the ones who needed it most, and giving it there in immeasurable abundance - made her a walking Guanyin, goddess of compassion and mercy. Yes, Mom learned to walk with power, with Dad by her side. She never did lose the "low talking," though.

At this moment, with her fingers running through my hair, her voice was even softer and lower than usual, as she told me to imagine a safe and beautiful place, going so far as to suggest a moss-carpeted stream bank to me - maybe some tall trees, butterflies, the sound of running water, and a breeze. Having gotten me started, she invited me to fill the rest in with whatever made me feel good inside.

Once I was "there," she told me to tighten and then release the tension in my toes, and then she brought my attention to my feet. She cupped the back of my head and told me to relax my calves, thighs, and stomach. Her fingers caressed my scalp as she told me to loosen my fingers, hands, and arms. She held my temples in two hands and told me to ease my jaw, cheeks, and tongue; my eyes, eyebrows, and forehead. From the tip of my toes to the top of my head, she took me on a journey of ultimate relaxation. I didn't know what we were doing, but I knew it felt good.

I had a lot of anxiety as a child - probably still do, but I have more tools in the shed now to keep it in check, and even make it work for me sometimes. As a child and young adolescent, almost anything could throw me into a negative spiral of impending doom and I paid for it in regular, debilitating stomach aches, nausea, and sometimes - in extreme cases - vomiting. Uncontrollable crying was another symptom of my crippling fears of failure (in anything) or rejection or judgment (from anyone).

I don't think she had a master plan in this exercise. I think Mom was a healer by nature, and simply drew from the tools she had at hand to help in whatever situation was before her, and in this situation, her daughter was working herself into hysterics and needed assistance in restoring her equilibrium. The result, though, was that a seed was planted.

How thankful I am to a mother who first showed me that when the world is falling apart around you, peace can still be found within. Even more remarkable was the eventual discovery that direction and guidance can be found there too.

“Though I do not believe that a plant will spring up where no seed has been, I have great faith in a seed. Convince me that you have a seed there, and I am prepared to expect wonders.”

The Chinese Tea House

I have a Chinese tea house, at the cliff's edge, overlooking the jagged and misty blue peaks of Wulingyuan in China. The air is rarefied there and bathes the senses. The lungs feel cleansed with each inhale, while stagnant thoughts, stuck energy, and untruths leave your body with each exhale.

The tea house is a low building, hunkered down among the Cypress, weeping willows, and crooked Red Pines that partially disguise its artifice and make it seem almost a natural part of the landscape - a kind of Hobbit hole of the East. But then the whimsical, circular entrance to the garden wall, ornately carved to contain dragon heads at your feet, and the yellow, clay-tiled roof that rises just above the trees, with its two levels of "flying eaves" at the corners, do seem to betray a modest assertion of joyful vanity that cannot be suppressed or fully hidden.

If my tea house were a sentient being, I imagine it would be humbly aware of, and most gladdened by, its own beauty - not just for its own sake, mind you, but for the peace it held inside for you.

Half of the building is supported by cleverly hidden pylons that make it appear to hover over a large koi pond that is edged with white pea gravel pathways and effusive chartreuse tufts of Japanese forest grass, tumbling like water over rocks down to the pond's surface. Masses of orange and red day lilies provide splashes of vibrant color at strategic points.

If I sit, as I often do, on the wooden breezeway that juts out over the pond, with the double shoji screen doors behind me slid wide, my feet dangle a few inches over the water. From there, I can see, off to my left and in the middle distance of the garden, an arched bridge spanning a narrowing of the koi pond, and a series of stone steps leading up to a tiny pagoda on a hill there that seems to offer higher perspectives, although I have not yet been there to see if it is true. The fish do swim in an eternal loop, there and back again, as far as the water will allow them, and as if to encourage me to follow, but they have yet to share with me the secrets of the stone pagoda. It seems I must go there myself. I made it as far as the bridge once, but felt called back to my tea house before I could go any further. And so the pagoda - for now - waits.

Here by me, sitting over the pond with feet dangling, there are roundish stepping stones that allow me to jump down right from the ledge of the tea house and cross the water with bare-footed ease - either to climb up the far bank to wander the garden, or to visit with and feed the large koi, who follow me from stone to stone. Stone lanterns light the scene at dusk.

To the right of the koi pond and garden, is a large flat gravel surface that leads all the way to the cliff's edge. There, a lone cherry tree clings, sculpted by wind into impossible ripples and swirls, almost appearing to wave and flap like a banner over the precipice. I can climb this tree - my toes have found all the right footholds - and lean out over the gorge, feeling the space stretch vast above and below me. There I can also feel the wind that buffets the tree day and night. I realized the first time I stood there, that the wind is not violent, and so the tree, whatever it may appear to be on the surface, is not “twisted” and “bent,” so much as it is “burnished” and “shaped.”

At the foot of the tree, just to its left, is also a small frog pond, ringed with field stones. In the summer you can see the eggs clinging in jelly-like masses with black "pupils" under the surface, while newly hatched tadpoles whip their tails around in the joy of new life. Sudden movement on my part will also send little frogs, cool and green as new spring grass, darting back into their watery realm - bloop! plunk!

Although you, an honored guest, would approach the tea house through the tile-roofed, white stucco garden wall with the round dragon entryway, I do not come in this way. I always enter the tea house ... from my mind.

This tea house exists only there. Influenced by places I have been, and things I have seen, yes, but purely imaginary in its unique totality. It is the grown-up version of what Mom told me to find all those many years ago: a safe and beautiful place inside myself, where peace and clarity reign.

Journey to the South

All of my meditations begin and end at my tea house and garden. I can leap off the cherry tree and fly upwards, exploring realms above the clouds. I can slip into the frog pond and dive deeply downwards, finding worlds upon worlds. I can simply stay in the tea house and sit at a stone basin of clear, sweet water overlooking the koi pond and garden, and wait for "them" to come to me. Who are "they"? Well it depends. They can be animal or human; friend, loved one, ancestor, guide, or shadow part of myself. But they all come with love and a gentle and profound wisdom that helps me dispense with illusions and wishful thinking, see to the heart of most any matter, and feel unconditionally loved, guided and supported through it all. Some might call them my subconscious, but I have questions.

Very early on in my meditative forays (spring of 2015), I had read that a popular thing to do among those who meditate is to visit the “Four Directions” (East, South, West, and North) because in many traditional societies across the globe, each of the Four Directions holds unique insights and wisdom. I admit to feeling a little bit foolish at first, but perhaps it was my upbringing between worlds, as a multi-racial person, and my years of anthropology training that first taught me that there is more than one universe of knowledge, more than one way of doing things and being in the world, more than one way of looking at it.

This is not at all the terrible idea that “my opinion is as good as your facts,” which threatens the very existence of democracy and civil society today. It is simply an acknowledgment that experience and wisdom exist in many places and spheres, and my upbringing and my education have made me open, and given me awareness of the poverty of one’s own narrow band of vision. In short, I had come to know that there was much I didn’t know. And a Buddhist monk would tell you that if you know that, you know more than most.

On this day, I slipped silently beneath the surface of my frog pond and dived to the bottom, where I emerged through a hole into a moist tunnel that appeared to lead out to a stream bed in the middle of a jungle. Not for nothing, but I noticed that I was surrounded by ancestors down there, males to the right - Grandpa! Uncle Sandor! The two Archies! - and females to the left - Grandma Wiltrude! GG! MOM!!!!!!! They felt real as real could be. They seemed to guard the entrance to this world and sent me joyously on my way.

Exiting the tunnel, whose opening faces East, I turned hard right and headed South, soon finding myself leaving the jungle behind and entering a desert landscape of impossible wildness and beauty. A herd of mustangs galloped before me in a wild circle of tossing heads and shaking manes. The sun was going down, turning the desert sky candy hues of purple, pink, and melon. Buttes and mesas were silhouetted like inky flourishes on the landscape. I took it all in and then turned away from the canyon before me and walked into the desert, the light turning flat and gray, until I came upon an unattended camp fire. I sat by the fire and waited. “The south will come,” I seemed to understand.

Almost immediately, I heard the approach of foot steps and looked up to see soft-shod feet enter the circle of firelight across from me. My eyes traveled upward and fell upon the countenance of an unnervingly handsome, and dare I say, barely clad, man - the picture of youth and human vitality, with skin the color of chestnuts and hair that fell in a sable sheet down his back. His ethnicity was ambiguous - like my own - but I felt I discerned more than one kind of East Asian there, and maybe some Native American as well. Multi-racial people are pretty good at sussing out each other’s level and type of admixture; it’s almost a hobby.

This man had an impish grin on his face. Suddenly, a laugh outright, with a flash of dazzling teeth made my heart stop. He thought it amusing that I found him so beautiful. I couldn’t believe it, and though this was a meditation, I felt real-world sheepishness to be caught out like this, with “zero chill.” But I have to tell you, to be “chill” in the presence of such a one could only betray the most dullard and prim tendencies, and if you don’t know now you do: I am neither dull nor prim.

He took a seat near the fire, whose light flickered warmly across his tattoos. I had never seen any like them, but they were distinctive enough that I felt compelled to draw them when the meditation was over. They covered his chest and shoulders in a yoke, or “boat-neck scoop” fashion, and were done in distinctive parallel “lines” with visibly bare space between them, almost like the text you are reading right now. Tiny triangles or points formed one line, and then what appeared to be squiggles formed a second line and maybe a third. There were also indistinct markings going down both shoulders that I couldn’t make out. I scribbled them in anyway.

And then a number of things happened: he left the fire and came back after a time a little out of breath and carrying a desert hare by the ears. He skinned it and roasted it on a spit over the fire. He cut a piece and held it out to me, jerking his hand slightly upward and toward my face, encouraging me to try it. I did and he laughed in approval as I marveled over the taste, so juicy, so well-seasoned. After we ate, he pulled out a long clay pipe, leaned back against a large dried tree trunk which lay on its side behind him, and looked contentedly at the stars.

I tried asking for a name (which I had read one was to do, if one encountered any “characters” on these kinds of mental journeys), but he simply smiled at me. I also asked if he had a gift for me, which was another suggested tactic. At this he put the pipe aside, sat up, spread his fingers wide and scooped them palm down through the sandy soil on either side of himself and then raised his hands again, watching the dirt slide back through his fingers. He picked up a handful of the soil, reached over, and let it shift and slide in a thin stream into my own outstretched palm.

Without speaking, he made me understand that I was to reconnect with the earth, ground myself, and not get lost in ruminations and worry (about Dad) or take my sheer physicality for granted for I was a spiritual being having a human experience, it was not the other way around. He told me to build a garden to remind myself of these things.

“Well, it’s not like I haven't been trying,” I thought to myself. But the soil he had given me was not very high quality either, like the soil in my own back yard. He seemed to be urging me not only to reconnect to the earth in a general sense, then, but to also know my small patch of it for what it was, see its potential, and act accordingly.

Now you might chuckle when I tell you that all of this was happening in the parking lot of a grocery store, but it is true. Having gotten what we needed for dinner, I was resting my eyes in the driver’s seat and waiting for the time to pass until I had to go pick up the boys at Taekwondo, and this entire scenario had played out on the screen within my mind in a mere 10-minutes of silent meditation.

As I pulled out of the parking lot and drove to the dojang, which was only a minute or two away, I began to feel a strange “pressure” in the space above and to the left of my forehead. It was not a physical pressure, so I struggle to find the words to describe it here. But if, for example, we have an “energy field” surrounding us, it felt like something pressing on the outside of it, maybe a foot away from my body - like a finger poking a block of Jell-O without actually penetrating it. There was something springy, almost like a boing, about it. I felt it press in, then bounce away - boing - then press in harder, and bounce away again. I tell you, I have never experienced anything like this before or since. And suddenly I heard myself say out loud, as I was turning the car into the dojang parking lot, “He’s going to tell me his name.” And then there was a hollow popping sound or really more of a popping “feeling” because I didn’t actually hear anything. But it felt like a thick, viscous bubble bursting, and I spoke out loud again, involuntarily, “Nam Toc.”

I shook myself from the experience and repeated, “Nam Toc. Nam Toc?? His name is Nam Toc? Is that even a name? What does that mean???”

I picked up the kids, brought them home, made dinner, and - for the most part - forgot about it. But that evening, I googled “Nam Toc” and found that “nam toc” is a Thai word for a savory, well-seasoned piece of meat. I felt a prickle arise in my spine as I remembered the rabbit. And then a new idea seized me: if Nam Toc indicated Thai origins, maybe I should look up indigenous Thai tattoos. “Are there any indigenous Thai tattoos?” I wondered. I had no idea.

I typed it in the search box, waited for half a second, and then, without a hint of drama, screamed and threw the phone away from me as if it were hot to the touch. It hit the leather of the couch and lay there, face up, compelling me to keep looking. Not that I could have looked away. For there were the tattoos that I had drawn in my journal, never before seen by me. I learned that they were called a “sak yant collar” and you can look it up online if you want to see one. Sak Yant tattoos have an ancient history in Indian and Thai Buddhism, and depict sacred geometry. The little “triangles” I had drawn are actually known as “gao yord” or “Buddha peaks,” and distinct parallel lines of writing and prayers are often tattooed beneath them.

I was so overwhelmed by what had happened to me that day that I confided breathlessly in my friend, Sung, who happens to be Korean.

“And then do you know what happened?” I texted furiously. “I found out that Nam Toc is a THAI word meaning a juicy, well-seasoned piece of meat. And then I looked up Thai tattoos and they were the tattoos from my drawing!!! The only thing is, he didn’t really look Thai. He looked more mixed, like me.”

I stared at the phone for a minute, willing him to read the text immediately and get back to me. And then, success! Three little dots began to ripple and shimmer in their bubble on the screen, indicating that Sung had read my message and was typing.

“Well,” his text said, when it came through, “I literally do not know what is going on right now but it seems like you’re having a pretty weird experience. I should probably tell you that Nam Toc - and actually, I would probably spell it ‘Nam Tuck’ or even ‘Nam Duck’ - is also a Korean guy’s name.”

“It is???” I asked, as the prickle began to travel up my spine again, this time reaching further. And then, almost afraid to hear the answer, I asked, “What does it mean?”

[send].

[silence].

[rippling dots…].

“Mean? Well, Nam means ‘south,’ like the direction, and Tuck is like…. a ‘virtue’ or ‘benevolent force.’ But more than that, it’s one that actually helps you, so like, I would translate it as ‘Helpful Virtue.’”

“WHAT!” I typed at the top of my lungs.

“Yeah. Sounds like your guy, Nam Tuck, is actually Helpful Virtue from the South.”

I burst into tears and didn’t stop for two hours. It still brings a tear to my eye to recall this first moment of recognition - that I had experienced something very profound and way beyond my ability to explain in scientific terms. I could dismiss it because I’m generally science-minded and don’t have an explanation for it. But consider this: a scientist who dispenses with data that don’t fit his or her worldview is no scientist at all. Clearly some of my long-accepted “theories” about how the universe works were turning out to be more like hypotheses that at least needed to be revisited.

And for the record, I still don’t have the answers about these remarkable experiences. As you can imagine, I have similar stories for the North, East and West, as well as many more now. But on this particular subject, I've also stopped needing to know. Some things, I have decided, are just better received as the gift that they are. It doesn't matter where they come from, or why, or if "they’re real” in any narrow understanding of what that word means. You’ll never get the right answers if you keep asking the wrong questions, and in this case the only right question was this: Does it help? If the answer is yes, then do it.

It does, and I did. I built a garden.

I billed it on social media as “The Great Gardening Rampage of 2015,” and none but my closest friends knew its origins or what it meant to me.

The Great Gardening Rampage of 2015

When the truck full of beige-colored pea gravel backed into our side yard, I walked out to the second-floor deck and held the iPad over the railing with the camera flipped forward so that Dad could watch the hydraulic rams lift the open box bed to a vertical position. Tons of gravel slid down the metal bed in a great cacophonous “whoosh” and rumble, forming an enormous heap just outside the access to the back of our lot.

“Oooooooh boy, look it look it,” cried Dad. “Wwwwwow!”

I flipped the camera back to me and smiled.

“What are you going to do with all that?” he asked.

I turned the camera back to the front and made my way carefully down the spiral stairs to the garden level so that I could pan the scene for him while I talked.

“Well,” I said, “remember how I was telling you that I’ve been trying to grow grass for eight years to no avail? I suddenly realized, ‘who needs grass anyway?’ I mean, really. Who needs it? Says who? So I started thinking about the rock and gravel gardens you see in the desert and in Europe and Asia, and thought, why not here? Why not simply accept the fact at long last that grass doesn’t want to grow here, and then make the most of it? So, as you can see, I’ve removed all the sod and laid out three little garden beds, ringed in stone, where I think something can grow. And I’ve just finished laying down landscaping fabric on the rest, and now all that I have to do is spread this gravel everywhere.”

“You did that all by yourself?” Dad asked with no little admiration, and I thought some nostalgia too. Dad was a “project” guy himself - or at least, he had been.

“Yep. Completely. I’m an archaeologist, you know; I do know how to use a shovel. And also,” I continued, carrying on a little joke of his own, “I got musk-els.”

Dad laughed, repeating the word “musk-els” under his breath in delight. He often repeated things that amused him under his breath, to savor the humor a little longer. Musk-els, in particular, had been delighting him for 75 years. I found him using it in a letter back home as far back as the 1940s.

Ever after, any time we talked on FaceTime, which was most days, he wanted a report and sometimes a “tour” of the garden, to see how it was coming. He was unfailingly enthusiastic about it. Indeed, I do believe that my garden was the best thing he had going that summer! I did not tell him that I considered it my Grief Garden.

You see, after my visit with Nam Tuck, and in accordance with his advice, I had taken every ounce of fear, dread and anticipatory grief that I felt about Dad slipping away from me and deposited it into this garden. It was not that he was at death’s door, or that he couldn’t still be amiable, curious and cheerful, for indeed he was. The slippage could be felt in his little forgetfulnesses, his flagging ability to keep up cognitively rigorous conversation, his fears and paranoias that no amount of reassurance or logic could dispel. Somehow, though he was still quite lively, I simply came to believe - nay, to know - that he was not much longer for this world and it felt like the end of my own.

But here I was, feeling remarkably better as the summer progressed. This garden project was no poking around with little gloved hands and a miniature spade. This was serious earth moving. I wore steel-toed boots and a “wife beater” to do it. I sweat like the dickens; my breath came hard and labored; my back and shoulders hurt at night. I made involuntary grunting noises as I pried up rocks the size of my head and heaved them out of the way. They landed with great earthen thuds. I used loppers and all of my body weight and tork-capacity to cut through tree roots as thick as my wrists. All of this, just to clear the way for more back-breaking digging.

Then there were the dozen or so trips to Lowes to get paving stones to line the garden beds; I loaded the back of the CR-V as far as I could and drove home riding frighteningly low in the rear, only to unload and head straight back for more - more stone, more soil, mulch, landscaping fabric, pins.

The digging, weeding, and planting were highly physical activities that released endorphins into my blood stream and helped keep me fit. The planning part consumed my waking mind. My skin bathed in the fresh, clean air and soaked up Vitamin D from the sun. I tan quickly and soon had a vital glow about me that made my outside more closely resemble my inside.

This wasn’t just a placebo effect. A study published in the Journal of Health Psychology reported that gardening was more effective at reducing stress and restoring mood than reading a book. As an avid life-long reader, myself, and one who has always turned to the written word for escape and salvation, that one really made me sit up and take notice. Another study that appeared in the Journal of Public Health found that working in a garden for just 30 minutes increased not only mood but also self-esteem. People who garden actually feel more worthy and purposeful than those who do not. It’s science!

My stress levels were undeniably lower as I turned my private little stretch of nature into a restful haven. I was able to do this because I was no longer fighting upstream; as paradoxical as it seems with all this shoveling and grunting going on, I was quite literally “going with the flow,” and this for the first time. I had accepted that we were not meant to have grass back there; I spent time at the nursery finding plants that were pleasing to me but also had an outside chance of surviving the soil and light conditions they would be inhabiting. I learned to love hostas, those plain janes of the gardening world. Who knew there were so many varieties, if you cared to look? Not I. There were the Patriots and the Blue Angels; the Pathfinder and the Striptease; the Wolverine and Paradigm; and who can forget the darling little Mouse Ears? Who wouldn’t want such a cast of characters in their garden?

I planted hardy desert grasses. I strategically placed my sun-loving silver mound, bachelor buttons, sea pinks, purple cone flowers, daisies, black-eyed Susan, irises and a Korean lilac - not so that I could see them where I wanted to see them, but so that they would live, and just maybe thrive. I filled spaces with sedum and other succulents, and put stepping thyme in the walkway for the bees.

I also bought a large container and made my own little “frog and fish pond.”

It occurred to me that every patch of ground has its own version of perfection, and it cannot be imposed upon. So does every life. You cannot submit it to artificial rules or demand specific outcomes. You must make the best of where you find yourself. If you show patience and perseverance, a willingness to accept what is, a trust in the growth process, and an understanding that whatever you nurture will grow, for better or for worse, you will find that no ground is truly infertile.

The Gift

And what do you suppose happened next? The birds came. Dozens of species - so many I couldn’t keep track. Sparrows, warblers, jays, cardinals, chickadees, crows, and many more I couldn’t identify, all colors of the rainbow. The squirrels and chipmunks defied my attempts to keep the bird feeders full, but I was feeling flush and benevolent and I did not begrudge them their winter fattening. By the end of the summer, I could sit at the dining table I had set up under the deck, where I was less noticeable to wildlife, and watch the birds swoop and dive, in and out - warbling, chirping, and whistling - shimmying in the birdbath, grabbing a quick bite and then flying back up into the branches of the hemlocks, rhododendron, and hydrangea to tell their friends. The constant twittering sounded lush, like water dripping.

As July moved in to August, the babbling brook of birdsong was underlain by the warm hum of buzzing bees, and suddenly I realized that my barren and obstreperous little plot of land was bursting with life, and that maybe it had really been I who was barren and obstreperous. Fighting the flow of things, making unreasonable demands - Irises should grow here! We should never lose our parents!

I had lacked the imagination to see things in a different way, to find or create beauty, and had robbed myself of the light of hope as a result. And so I festered in darkness. But I looked out now and saw a promise - of healing and joy to come (eventually, eventually), but more immediately, that even in the midst of a storm, there can still be brightness and beauty found.

I, in fear of death, had brought something wildly, beautifully, and movingly to life. “My grief did that,” I marveled. And where was my grief, anyway? I looked around and found it had grown significantly smaller, more manageable, confirming my suspicions once and for all: that grief is just the pain of love that has nowhere to go.

So if that was true, I thought, then it wasn’t grief that built this. It was actually love. That means further that this was not a “Grief Garden,” as I had originally been thinking, but a physical manifestation of how I felt about Mom and Dad. It was a monument to love.

“Grief is the pain of love that has nowhere to go.”

My garden had graciously taken my grief within itself and cleaned it - giving me something beautiful in return. I got to thinking about transformation - a neutral concept, change, neither good nor bad, just existing. Maybe Nam Tuck, my Korean Helpful Virtue from the South, really knew what he was talking about.

One day, as the weather began to turn crisp, I noticed something new growing in one of my garden beds. It was not something I had planted and my first instinct was to pull it, as a weed, but something stayed my hand as I thought, “Wait. Wait and see what it is first.”

I waited for days, and then weeks, as the mystery plant grew larger and larger - a single stalk, with leaves not unlike those of a maple tree, but rather bigger. The suspense was great. And then a large bulb formed at the tip, and it looked a little like a Chinese Lantern plant, only green, with papery shell in an acorn shape, concealing something that was clearly growing plump within. My excitement grew. What on earth could it be? And then one morning toward the end of September, I left the house with Seu (5) and stopped dead in my tracks. The pod had opened and from it had emerged a large white flower the size of a dinner plate, with a fuchsia center. I was beside myself with joy. I took a picture with Seu for scale and posted it on Facebook, “YOU GUYS!!! LOOK WHAT JUST HAPPENED TO MEEEEE! I did NOT plant this in my garden. Today’s small win.”

And what if I told you that it turned out to be a hardy hibiscus - the national flower of South Korea?

Like, Comment, Share!

Although the buttons below work, Squarespace is currently struggling with a bug that erases the tracking at random. Please don’t let low or no numbers shown deter you. Likes and shares still help boost my visibility, even if the numbers don’t stick around to show it. Thank you!